Extractions in dogs and cats are categorized as simple and surgical. Simple extractions are performed where alveolar bone removal is not necessary to facilitate successful extraction. Examples include deciduous teeth, mobile teeth and incisors.

Dr. Brett Beckman holds advanced degrees as a fellow in the Academy of Veterinary Dentistry, diplomate of the American Veterinary Dental College and a diplomate of the American Academy of Pain Management. He has published numerous peer-reviewed articles in the field of veterinary dentistry, oral surgery and pain management. He owns and operates a companion animal and referral dentistry and oral surgery practice in Punta Gorda, Fla., and sees referral cases at Affiliated Veterinary Specialists in Orlando, Fla., and at Georgia Veterinary Specialists in Atlanta. He lectures internationally on topics related to dentistry and pain management and operates the Veterinary Dental Education Center in Punta Gorda, Fla. For more information go to www.veterinarydentistry.net

Extractions in dogs and cats are categorized as simple and surgical. Simple extractions are performed where alveolar bone removal is not necessary to facilitate successful extraction. Examples include deciduous teeth, mobile teeth and incisors.

Radiographic evaluation has fast become a common facet of veterinary dentistry and only practices that utilize dental radiography can practice quality dentistry. Interpretation of radiographic changes that occur in the tooth and surrounding bone take many forms.

The largest portion of our dentistry case load in everyday practice involves the treatment of periodontal disease. No other oral malady will present itself more commonly. At the same time proper evaluation of the stage of periodontal disease is determined with probing, visual examination and radiographically.

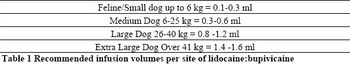

This author commonly uses lidocaine and bupivicaine combined in the same syringe for regional oral nerve blocks. Lidocaine is not desirable as a sole agent due to its limited effect post administration (1-2 hours).

Prevention and treatment of periodontal disease can only be accomplished through regular professional care under general anesthesia. Multiple steps are involved in this process and the veterinary/technician team plays a vital role in ensuring quality control, efficiency and completeness.

Benign and malignant masses are commonly encountered in the oral cavities of dogs and cats.

Spontaneous oral hemorrhage without trauma is an uncommon finding.

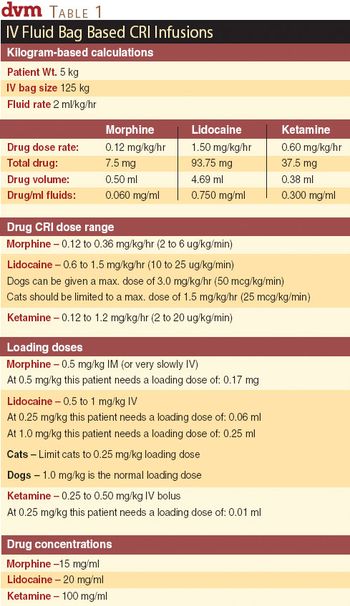

Veterinary patients with chronic oral disease requiring oral surgery benefit tremendously from what I call the analgesic triad: continuous rate infusions (CRIs), physiologically targeted post-operative analgesics and regional nerve blocks.

Medical management is possible, but often these cases result in extractions.

An unusual presentation results in an unusual diagnosis.

Root-canal therapy was chosen to avoid surgery on the patient mentioned in the first two parts of this series. While root canal is very successful, not all cases respond. Additional therapy may be required.

When weighing the therapeutic options in treating this unusual gingival lesion, there are several considerations to explore.

This is the first article in a series of case presentations designed to address a variety of oral conditions and discuss the pathophysiology involved.

Dental radiology is the cornerstone of quality veterinary dentistry.

Many of us rely on verbal messages in the exam room as the sole means of communication. In so doing we fail to effectively reach the other 60% of clients that learn best by visual means.

The utilization of regional nerve blocks for oral surgery in dogs and cats is synonymous with quality patient care.

Proper professional dental prophylaxis and detailed periodontal therapy is a must for every small animal practice.

Oral fracture repair in dogs and cats has traditionally taken many different forms. Pins, plates, screws and external coaptation devices are all methods previously employed that are relatively invasive.

Simple extractions in some cases are not always simple as their name implies.

Feline chronic gingivo-stomatitis represents a painful oral condition in cats that therapeutically has only responded predictably to surgical extraction of all premolars and molars.

Simple extractions in some cases are not always simple as their name implies.

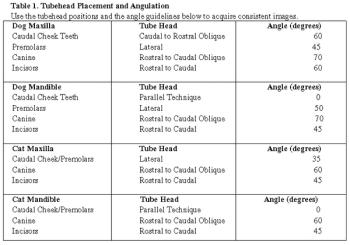

Veterinary dental radio-graphy traditionally has been one of the most frustrating aspects of veterinary dentistry.

Oral surgery in canine and feline patients often requires extended periods of anesthesia necessitating optimal anesthetic management.

The utilization of regional nerve blocks for oral surgery in dogs and cats is synonymous with quality patient care.

Part II discusses some of the common agents used for managing pain associated with oral surgery in dogs and cats.

Feline chronic gingivo-stomatitis is a painful oral condition in cats that therapeutically has only responded predictably to surgical extraction of all premolars and molars.

Oral surgery in canine and feline patients often requires extended periods of anesthesia necessitating optimal anesthetic management.

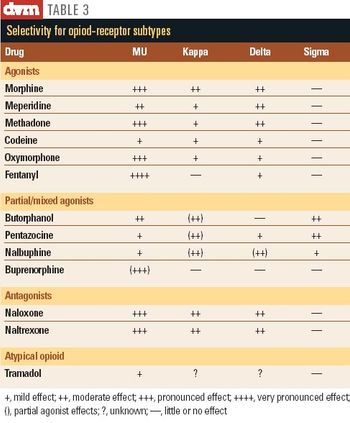

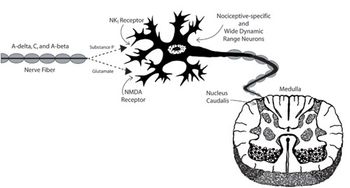

Six of the most common agents used for managing pain associated with oral surgery in dogs and cats will be discussed in this third article of a series on pain management. They are the opioids (opiates), the Cox-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), the 5-Lox selective NSAIDs, the alpha-2 agonists, the NMDA-receptor antagonists and the serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

The use of regional nerve blocks for oral surgery in dogs and cats is synonymous with quality patient care.

After oral surgery, nociceptor response is expected to be greatly enhanced.