Uroendoscopy (Proceedings)

Direct visualization of the lower urinary tract can be important for the diagnosis and treatment of many disease processes. Evaluation of the urinary bladder, ureters, and proximal urethra is possible via surgical exploration; however uroendoscopy is a minimally-invasive technique which allows assessment of the lower urinary and distal reproductive tract.

Direct visualization of the lower urinary tract can be important for the diagnosis and treatment of many disease processes. Evaluation of the urinary bladder, ureters, and proximal urethra is possible via surgical exploration; however uroendoscopy is a minimally-invasive technique which allows assessment of the lower urinary and distal reproductive tract. In some situations, uroendoscopy may be valuable for the assessment of the upper urinary tract as in the case of unilateral renal hematuria. Uroendoscopy allows visual evaluation of the vaginal vestibule, vagina, entire urethra, urinary bladder, and ureteral openings. In some cases, the endoscope may be passed into the ureters for luminal evaluation as well. Diagnostic and therapeutic procedures may be performed via urinary endoscopy including biopsy, urolith retrieval or lithotripsy, and laser surgical procedures. Uroendoscopy can be a valuable part of the diagnostic and therapeutic management of urinary tract diseases and can yield different information than that gained from other imaging modalities due to magnification of the luminal surfaces.

Indications

Many diseases of the urinary tract lend themselves to cystoscopic evaluation. While it is often difficult to pass an endoscope into the ureters, it is possible to make some evaluation of the quality of the urine passing from one kidney or another by observing the pulsatile urine flow from the ureter openings. This is particularly relevant in cases of renal hematuria when only one kidney may be involved. Other indications for uroendoscopy include urinary incontinence, persistent hematuria, recurrent urinary tract infections, multiple types of dysuria, urinary tract obstruction, vulvar or penile discharge, and urethral or bladder masses. The potential for breakdown and retrieval of uroliths also makes uroendoscopy useful in these cases. In females, it is easy to confirm that all stones have been removed following voiding urohydropulsion.

Equipment

Rigid endoscope systems require a light source, camera, video monitor, and preferably an image capture system that allows for data storage onto CD or DVD. There are several manufacturers of these systems and they are often purchased as part of a package with the endoscopes. Some incompatibilities exist between systems, so it is best to use components from the same manufacturer or verify their compatibility prior to purchase.

The best light sources for video uroendoscopy are xenon with automatic intensity adjustment. Halogen light sources can be used as well and are generally less costly, but have a lower intensity and produce lower image quality than xenon lights, especially when using smaller diameter cystoscopes. Although many rigid and flexible endoscopes have eyepieces, a camera and video system is essential for proper detailed viewing and documentation of uroendoscopic studies. Cameras are generally available in one- or three-chip models. The three-chip has higher image quality due to 3-color capture and processing and produces better images in low-light conditions, although one-chip models are adequate for most applications. Ideally, the camera has a focusing system and image capture controls mounted on the operating head, although some have foot-pedal operation. A wide range of image capture systems are available from state-of-the-art high definition video to those that record only still images. Since dynamic imaging is desirable in uroendoscopy, a system which provides capture and recording of both still and video clip images is preferable.

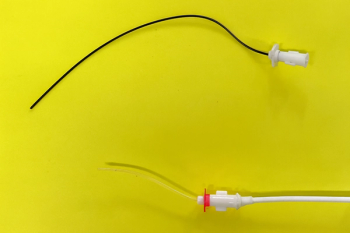

Both rigid and flexible endoscopes may be used. Rigid cystoscopes consist of three parts, the telescope, sheath, and bridge. These may be separate components or integrated by the manufacturer. The glass fiber telescope provides an angled view of 0°, 12°, 30°, or 70° from the tip of the scope. The authors prefer 30° which allows for visualization of all areas of the bladder with less manipulation as well as good visualization of the working field when using instruments. The sheath contains the irrigation and operating channels and the bridge has the light-source and camera connections as well as the instrument port. Rigid endoscope systems come in a variety of diameters and lengths. For small animal endoscopy, three sizes are generally recommended: 4.0mm x 30cm for medium to large female dogs, 2.7mm x 18cm for small and medium female dogs, and 1.9mm x 18cm for female cats and male cats with a perineal urethrostomy. Additionally, a flexible or semi-flexible 5fr scope may be used to examine male cats. Male dogs with urethras that will accommodate an 8fr diameter catheter can be examined using a flexible 7.5fr x 45cm human ureteroscope or other flexible endoscope of similar size.

There is a large variety of accessories and instruments available for rigid endoscopes. At least one good quality biopsy forceps which fits through the operating channel is required for obtaining tissue samples. In addition, stone retrieval baskets, grasping forceps, and cautery tips are available.

Care of uroendoscopic equipment is similar to the care of other endoscopes. Rigid scopes are relatively durable; however, the small size of many of the instruments makes them especially fragile. Caution must be exercised to prevent over flexion of the instruments or excessive force in deploying and retracting them. The very small flexible and semi-flexible endoscopes are also extremely fragile and need additional protection during cleaning and sterilization.

Patient Preparation and Procedure

Female Dog and Cat

Uroendoscopy can be performed with the patient in dorsal or lateral recumbency. The endoscopist is generally seated at the caudal end of the animal and the tail is secured out of the operating region. The external genitalia of the anesthetized patient is shaved and surgically prepared. The use of sterile technique is important to minimize iatrogenic contamination of the urinary tract. The endoscope is either gas or liquid sterilized and sterile gloves are worn during the procedure. Sterile 0.9% NaCl is passed through the irrigation channel to distend the anatomy and improve visualization. The endoscopist assembles the scope and its components and attaches the light and camera cables. The irrigation and efflux lines are attached and the scope is liberally coated with sterile water-based lubricant. The scope is passed into the vaginal vestibule and the vulvar folds are gently grasped around the scope to allow for fluid distension of the chamber.

Normally, the mucosa of the vestibule is light pink in color and smooth. The vaginal opening, surrounded by a ridge of tissue, the cingulum, is seen at the craniodorsal aspect of the vestibule. Ventral to this is the smaller urethral opening. There may be a thin band of tissue crossing the opening dorso-ventrally of the vagina which has been called a hymenal membrane. A thicker band referred to as the mesonephric remnant is often associated with abnormalities of development of the urethra and ureter. Most patients with ectopic ureter(s) have this thick band (Cannizzo, 2003). Either of these bands potentially may be a cause of breeding failure. The urethral opening is often covered by a dorsal fold of tissue in the intact female dog, is often exaggerated in size during heat, and should not be interpreted as a mass lesion. Lateral to the urethral opening are fossae which may contain crypt-like areas. These can be normal findings and caution should be exercised to avoid mistaking these for ectopic ureter openings.

Next the cystoscope is passed into the vagina, though this may be deferred to last in those with obvious discharge. The vaginal opening is encircled by a ring of fibrous tissue called the cingulum. Beyond the cingulum the vaginal mucosa is pink with a prominent longitudinal fold running along the dorsal wall. The scope is passed cranially until the external uterine orifice at the caudal aspect of the cervix is reached. This has a folded appearance and passage of the scope beyond this point may be difficult and is rarely performed during routine urologic examinations.

The scope is redirected into the urethra and slowly passed cranially into the bladder. The urethra also has a dorsal fold and generally has smooth, light pink mucosa. The length of the urethra may vary between normal dogs. Once the vesicourethral junction is reached, the bladder is drained of urine and debris and redistended with saline to provide a clear view. Urine is generally heavier than saline and pools in the dependent aspect of the bladder, obscuring structures in this area. Distension of the bladder is essential to get an adequate evaluation of the ureters and bladder wall; however, over-distension may lead to tearing of the urothelium and hemorrhage. To prevent this, the bladder should be manually palpated through the abdomen by an assistant and distension ceased when it is slightly firm. If bleeding occurs, the bladder should be drained of fluid and chilled saline infused to induce vasoconstriction and reduce the impact on visibility. The infusion of cold fluid may cause the patient's body temperature to drop, and this should be closely monitored especially when multiple cycles of chilled fluid are infused and drained.

When the bladder is fully distended the trigone is examined. The ureters are located dorsolateral to midline as two crescent-shaped slits in the bladder wall. These two "C"-shaped structures should be facing each other as mirror images. An inverted V- or Y-shaped ridge may run cranially from the openings and join at midline. Verification of their patency should be made by observing the pulsatile urine flow from each ureter. The cystoscope is then passed cranially to the apex of the bladder and the entire bladder wall is examined. The bladder mucosa is light pink with a fine vascular pattern. Occasionally the bladder wall will be semi-transparent and abdominal organs may be faintly visualized from the lumen. It is important to examine all areas of the bladder interior in order not to miss small lesions or calculi which may fall to its dependent aspect. Manual palpation and manipulation of the bladder through the abdomen can assist in a full evaluation. After completion of the exam, the efflux channel is opened and the fluid is drained from the bladder.

Male Dog and Cat

Uroendoscopy of the male is generally performed with a flexible endoscope. An assistant may be required to exteriorize the penis from the prepuce and atraumatic hemostats may be necessary to maintain retraction, particularly in the male cat. The endoscope is prepared and lubricated as with the female and is introduced directly into the external urethral orifice. Infusion of saline facilitates distension of the urethra ahead of the scope. It is important not to use the scope tip itself to dilate the urethra as this can cause injury to the delicate urothelium which may be interpreted as lesions. As the scope is slowly passed from the perineal urethra into the prostatic urethra of the dog, tiny prostatic duct openings may be noted in the mucosa. These indentations are generally not seen in the male cat. Examination of the trigone, ureters, and bladder lumen are as with the female, but may be difficult due to the small size of the endoscope in relation to the size of the bladder lumen. Care must be taken to keep the tip of the scope close to the bladder wall to avoid missing lesions.

Abnormal Appearance - Uroendoscopic Lesions

Several anatomic abnormalities can be observed using cystoscopy. The most widely recognized is the presence of ectopic ureters. Although several imaging modalities have been developed for the diagnosis and locating of ureteral ectopia, computed tomography and uroendoscopy have been found to be the most reliable (Samii, 2004). Ectopic ureter openings may be seen at any point from the vesicourethral junction to the vestibule. Many have large openings which can accommodate the diameter of a cystoscope. Care must be taken to differentiate the urethra from these large ureters. Based on embryology, ectopic ureter openings within the urethra are always dorsolateral and the path to the bladder ventral.

Within the vestibule, small white nodules may be noted, particularly in those patients with chronic or recurrent urinary tract infections. These are often lymphoid in nature on histopathology and are likely secondary to the inflammatory process. Similar nodules are sometimes seen in the urethra and bladder. Presumptive abscesses may be noted in the wall of the bladder by their "fried egg" appearance, central pallor with a hyperemic rim around the nodule. These lesions may be biopsied and cultured to look for bacterial infection, and occasionally have been read as lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates.

Mass lesions may be found within the vestibule, vagina, urethra, and bladder. Malignant neoplasia and benign or inflammatory polyps can look similar on gross examination, so it is important to sample all abnormal tissues. Proliferative urethritis can resemble transitional cell carcinoma both in clinical presentation and cystoscopic appearance (Hostutler, 2004) though there are subtle cystoscopic differences.

Small uroliths are sometimes found on cystoscopic examination, despite the absence of ultrasonographic or radiologic evidence. Since most stones will fall to the dependent area of the bladder during examination, it is important to thoroughly evaluate this area. Assessment of urolith size and feasibility of urohydropulsion can be made at this time.

Additional abnormalities that may be encountered during cystoscopic examination include foreign material, ureteroceles, urachal diverticula, and the glomerulations characteristic of idiopathic cystitis in cats. Care must be taken to avoid interpretation of iatrogenic lesions from the uroendoscopy procedure.

Advanced Diagnostic Procedures and Interventions

Additional procedures may be carried out during uroendoscopy. These should be performed after a thorough assessment of the urinary tract is completed due to the risk of secondary hemorrhage obscuring the view. Biopsy of lesions is the most common using a flexible biopsy instrument passed through the instrument port of the scope. Unfortunately, these samples are usually quite small so several biopsies should be obtained for adequate analysis. An alternative is to identify a target area for biopsy, remove the telescope from the sheath, and advance a larger biopsy instrument through the sheath to the desired area – in this case the biopsy is done without direct visualization. Another alternative is to pass the scope up to the mass lesion and use suction to obtain an aspiration biopsy through the operating port. The smallest flexible and semi-flexible endoscopes do not have instrument ports, so biopsy may be necessary using ultrasound or fluoroscopic guidance in male cats and small male dogs.

If the ureter is dilated enough to allow passage of the scope into its lumen, a syringe may be attached to the instrument port and urine sterilely collected.

Several procedures may be performed to facilitate removal of uroliths. If the stones are small enough, they may be retrieved using a basket instrument or flushed from the bladder via urohydropulsion. Endoscopic evaluation of the urethra and bladder prior to urohydropulsion can facilitate passage of stones by lubricating and dilating the urethra. Single stones may be removed using grabbing instruments as well. Laser or electrohydraulic lithotripsy may be performed to break the stones into smaller pieces which may be safely flushed from the bladder (Adams 2008; Defarges 2006, 2008; Grant 2007). A final evaluation should be made around the bladder lumen, particularly of the dependent areas, to determine if all uroliths have been removed before completing the procedure.

The use of injectable bulking agents to treat canine urinary incontinence has become more widely available in the last decade. The most common agent is bovine cross-linked collagen (Contigen®, C. R. Bard, Inc. Covington, GA), although other materials may be available such as Teflon paste. The material is injected through a needle passed through the instrument port of the cystoscope and embedded into the submucosa of the urethra near the vesicourethral junction. Visualization of the procedure using cystoscopy is essential for adequate placement and filling of the injection sites. Additional information on injectable bulking agents is available elsewhere in this text.

Urethral stricture can occur secondary to trauma, surgery, or the lodging of uroliths in the urethra. Strictures can be identified by uroendoscopy and those that are too proximal for surgical correction can be treated using balloon dilation. Follow-up evaluation of the affected area is important to assess the effectiveness of treatment.

Some surgical procedures have been described in dogs using cystoscopy. Electrocautery of bleeding vessels and removal of masses has been performed (Cerf 2007; Upton 2006; Elwick 2003). The ablation of the wall of ectopic ureters to a more cranial position using a neodymium or holmium: yttrium-aluminum-garnet (YAG) laser has also been performed in both male and female dogs (Berent 2007, 2008; McCarthy 2006). Use of a laser in cystoscopic procedures including lithotripsy and tissue resection requires cystoscopic experience and advanced training and is currently available at limited facilities around the United States.

Post-Operative Management and Complications

Despite strict attention to sterility, the mild to moderate trauma to the urinary tract and the proximity of the anus may increase the likelihood of iatrogenic contamination during uroendoscopy. It is therefore recommended to place patients on 5-7 days of broad-spectrum antibiotics after the procedure. Alternatively, patients may have urine cultures evaluated 2-5 days after the procedure.

Both dogs and cats may experience a moderate amount of discomfort and pollakiuria after uroendoscopic procedures. Pain medication such as a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug or mild opiate may be used for 2-3 days. In addition, mild hematuria may occur in patients after cystoscopy. This is generally short-lived and self-limiting but owners should be advised of its presence.

Several complications may arise during uroendoscopy. The most common complication is failure to be able to safely advance the cystoscope through the lumen of the urethra. Lodging of the endoscope in the urethra can be avoided by proper selection of scope size for the patient and appropriate lubrication. The endoscope, whether flexible or rigid, should never be forced proximally through the urethra. This can lead to urethral damage or "hair-pinning" and lodging of a flexible scope in the urethra. Gentle pressure and especially in the case of males, proper use of fluid to dilate the urethra ahead of the scope should be sufficient to allow for passage. If this is not successful, a smaller diameter scope should be used.

Perforation of the lower urinary tract is also a risk with uroendoscopy. This is particularly a risk in patients with a severely diseased urethral or bladder wall. The endoscopist must be attentive to the degree of fluid distention in the bladder and release any over-filling through the efflux channel. Depending on the size of the damage, surgical repair may be necessary to correct a bladder tear. Rupture of the urethra can also occur, but may not require surgical intervention. Placing a urinary catheter for several days may be sufficient to allow for healing of the defect. The careful selection of an appropriately-sized scope and gentle technique will minimize these risks.

References

Adams, L.G., Berent A.C., Moore, G.E., et al. 2008. Use of laser lithotripsy for fragmentation of uroliths in dogs: 73 cases (2005-2006). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 232(11):1680-7.

Berent, A.C., Mayhew P., Matthew I., et al. 2007. Cystoscopic-guided laser ablation of ectopic ureters in 12 dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 21(3):600.

Berent, A. C., Mayhew, P.D., Porat-Mosenco, Y. 2008. Use of cystoscopic-guided laser ablation for treatment of intramural ureteral ectopia in male dogs: four cases (2006-2007). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 232(7):1026-34.

Cannizzo, Karen L., McLoughlin, Mary A., Mattoon, John S., Samii, Val F., Chew, Dennis J., DiBartola, Stephen P., 2003. Evaluation of transurethral cystoscopy and excretory urography for the diagnosis of ectopic ureters in female dogs: 25 cases (1992-2000). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 223(4):475-81.

Cerf, D.J., Lindquist, E.C., Straus, J.H. 2007. Ultrasound/endoscopy-guided diode laser ablation of nonresectable distal urinary transitional cell carcinoma in 19 female dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 21(3):600.

Defarges, A., Dunn, M. 2008. Treatment of urethral and bladder stones in 28 dogs with electrohydraulic lithotripsy. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 22(3):731-2.

Grant, D.C., Were, S.R., Gevedon, M.L. 2007. Holmium:YAG laser lithotripsy for urolithiasis in dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 22(3):534-9.

McCarthy, T.C. 2006. Peer-reviewed - Transurethral cystoscopy and diode laser incision to correct an ectopic ureter. Veterinary Medicine 101(9):558-9.

Messer, J.S., Chew, D.J., McLoughlin, M.A. 2005. Cystoscopy: Techniques and clinical applications. Clinical Techniques in Small Animal Practice 20(1):52-64.

Samii, Val F., McLoughlin, Mary A., Mattoon, John S., Drost, William T., Chew, Dennis J., DiBartola, Stephen P., Hoshaw-Woodard, S. 2004. Digital fluoroscopic excretory urography, digital fluoroscopic urethrography, helical computed tomography, and cystoscopy in 24 dogs with suspected ureteral ectopia. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 18(3):271-81.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.