EPM: The devil is in the diagnosis

Its 'the great imitator' because of varied clinical signs, intensity.

Equine protozoal myelo-encephalitis (EPM) has been a prominent neurological disease of horses for nearly 15 years. During this period, numerous bits of information have emerged about the causative organisms, their lifecycles, hosts and transmission. The veterinary community has made significant advances in the areas of treatment and rehabilitation.

Photo 1: This horse was diagnosed and treated successfully for EPM but suffered severe muscle loss on the right side of the rump involving the gluteal muscles. The nerve damage to these muscles is permanent; they cannot regrow.(Photos: courtesy of Dr. Kenneth L. Marcella)

The problem, however, is that EPM seems to remain as difficult to diagnose accurately as it ever was. EPM has been called "the great imitator" because it can present in many ways with varying clinical signs of differing intensities.

There are numerous tests available but even these have limitations. Currently, "there is no perfect test for EPM," says Dr. Sharon Witonsky of the Equine Field Service group at the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine.

Photo 2: A thermography scan of a horse with an active EPM infection shows cooler (bluer) muscle on the right side of the hip and rump, indicating a reduction of nerve stimulation and resulting decrease in blood flow and activity to these muscle groups.

EPM is a disease of the central nervous system caused by protozoal organisms. The majority of cases are caused by Sarcocystis neurona but recent work has shown some horses are affected by Neospora hughesi, another protozoan closely related to Neospora caninum. Similar clinical signs are seen with both organisms. The main host for S. neurona is the opossum (the definitive host for N. hughesi is not yet known), and horses are infected through the consumption of contaminated water and/or feed and hay.

Other hosts for these protozoan organisms have been implicated as possibly contributing to this disease and include armadillos, skunks and cats. Once S. neurona or N. hughesi enter the horse, they migrate to the central nervous system and can cause inflammation and damage anywhere in the brain and spinal cord. This fact leads to the varied and often confusing array of clinical presentations of EPM.

Horses with EPM can exhibit ataxia (incoordination) that can range from subtle to profound. They can show spasticity evidenced by stiffness or lack of fluidity in movement with stilted, slow or awkward limb placement, abnormal gaits and lameness. This incoordination can become worse when the head is lifted, and the gait abnormality or weakness is accentuated when the horse is walked up or down slopes.

Because damage to the spinal cord results in a "disconnect" to peripheral nerves, muscle atrophy is seen with EPM. Again, because the damage to the cord is random based on the para-site's movement, the muscle loss seen in EPM generally is asymmetrical and can vary in location and amount.

The muscles of the hindquarters and top line seem to be the most commonly affected or noticeable, though cases involving the neck, shoulder, forelegs and even the facial muscles have been reported. Other more subtle signs also can be encountered with EPM. Paralysis of the muscles of the face, eyes or mouth can be seen with associated drooping of the ears, eyelids or lips. Horses can have difficulty swallowing or breathing due to lack of nerve stimulation to muscles of the throat, larynx and associated structures.

Horses can exhibit only mild signs like abnormal sweating, head tilt or abnormal mentation, loss of sensation in various body parts, or the signs may be severe such as seizures and collapse. It is easy to see that EPM can have a wide variety of presentations that cause the practitioner problems when trying to accurately diagnose this disease.

Other signs to consider

There are other causes of neurological signs in the horse that should always be considered and either ruled in or out when progressing through the work-up of a potential EPM case. Fortunately, many of these other conditions have very accurate tests available and usually can be diagnosed more easily then EPM.

Eastern, Western and Japanese encephalitis and equine herpes virus can cause similar clinical signs but good titer tests are available.

West Nile viral infection can mimic many EPM signs, but a simple blood titer test will provide confirmation of this diagnosis.

Botulism, lower motor neuron disease, rabies, "wobbler syndrome" and a few lesser-seen conditions such as some toxins, tumors and trauma also may present with EPM-like signs, but history, disease progression and other tests (titers, radiographs/myelogram, additional blood values) usually help the clinician differentiate between these causes of neurological disease.

This leaves EPM as a "back-door" diagnosis in many cases. Additionally, EPM has become an all-too-common diagnosis for muscle weakness, poor balance, poor performance or behavioral issues in sport horses, even without any other evidence of neurological signs.

Many times, owners, trainers and even veterinarians evaluating the weak, imbalanced or poorly performing sport horse seize upon an EPM diagnosis and initiate treatment based on vague signs and without a definitive diagnosis.

Yet here is the problem: Definitive EPM diagnosis sill remains difficult, especially in the early stages or in cases with mild, vague or subtle clinical signs.

"There is no excuse, however, for not doing a thorough physical examination and working your way through an appropriate problem list when dealing with a potential EPM case," according to Mark Chrisman, DVM, Dipl. ACVIM, of the Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences at the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine. This work-up should involve a complete physical exam, the importance of which cannot be overstressed, with appropriate tests for some possible alternative diagnoses as well as tests for EPM.

Tests present challenges

Testing for EPM remains problematic, though, in that numerous problems and issues exist with just about every test available.

The serum antibody test for EPM is run on a sample of blood, and it detects circulating antibodies to S. neurona. A negative test means that the horse in question does not have EPM, unless it is early in the disease process and the body has not yet had time to make antibodies or if the disease is well localized in the central nervous system and the peripheral immune system has not been "exposed" to it yet.

This may be difficult to explain because the parasite must enter the body through the digestive system, and it would seem logical that on its way to the central nervous system some immune system stimulation and recognition should occur. But there are enough reports of initially tested EPM negative horses that became positive on retest to make this an important point to consider.

The horse in question also could be one of the small number of cases caused by N. hughesi or other protozoans. A positive serum antibody test often is seen as not very helpful because it is now known that 30 percent to 60 percent of all horses are exposed to S. neurona during their lifetime. The vast majority of these animals will make antibodies to this parasite, and their immune systems will mount a successful challenge so they will never develop EPM.

Studies indicate that only about one quarter of 1 percent of all horses (0.14 percent) will actually develop the disease. Crisman and Witonsky would suggest that it is precisely these statistics, however, that do make the serum antibody test a useful field diagnostic tool for EPM diagnosis.

If a high percentage of horses will have a positive serum titer for EPM yet a very small percentage of horses will actually have the disease, and if EPM generally causes at least some neurological signs in the truly affected horse, then the clinically diagnosed horse, based on a thorough physical examination, with a positive "high" serum titer, will have a very high likelihood of actually having EPM, while the horse with vague problems, no neurological signs and a positive titer will not.

Progression of signs

"In the field, I diagnose EPM horses based on clinical signs and a high titer," Witonsky says.

The progression of signs also can be a good diagnostic indicator, in that an examination done on the first visit when blood is taken for a titer can then be repeated a few days later when results (assuming a positive titer) have returned from the laboratory.

The EPM horse will very possibly show some neurological progression of signs between visits that can sometimes help the practitioner, especially if those neurological signs were not very apparent at the initial examination. Progression of signs (though common) is not required for EPM diag-nosis; however, many clinicians choose to progress to more advanced testing.

Western blot analysis of central spinal fluid (CSF) has been the "gold standard" in EPM diagnosis for years. This test verifies the presence of the protozoal parasite in the central nervous system, which is the classic definition of EPM disease. This testing methodology has been more rigorously evaluated than any other tests currently available.

While there are other tests out there (Polymerase chain-reaction [PCR] on spinal fluid, IgM ELISA, indirect fluorescent antibody testing [IFAT] and others), "the CSF western blot is the test that we know the most about," according to Witonsky, so it continues to be the standard even though there are issues about its interpretation.

"There is potential for peripheral blood contamination, some horses may have antibodies cross over from their serum to the CSF," explains Witonsky as she lists potential problems for western blot CSF analysis. "It is also possible that a horse could be very early in the disease process and not yet mount an antibody response in the CSF."

A University of Pennsylvania New Bolton Center study found that a few as eight red blood cells per microliter (roughly one millionth the concentration in peripheral blood and far too few to be seen in a CSF sample) can be enough to contaminate a spinal tap and cause a false-positive result. These problems, along with the additional risk to the horse and the financial cost, have led to a significant reduction in the number of CSF taps being done for EPM diagnosis.

"We used to do them (spinal taps for EPM) routinely, maybe three to four per week, but we are now down to maybe a few tests per month," says Crisman.

Newer tests

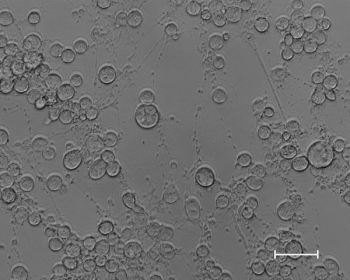

The newer tests show promise and may help because these tests, like the IFAT being run at the Diagnostic Laboratory of the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of California-Davis and the SAG-1 ELISA (Antech/Ellison), may be able to give clinicians some idea about active infection rather than past exposure titers. The indirect fluorescent antigen test (IFAT) offered at UC- Davis uses whole merozoites from an S. neurona SAG-1 positive strain (SAG-1+) as the antigen. The laboratory reports a titer and an odds ratio that gives the clinician a likelihood of active EPM disease. The SAG-1 ELISA, developed by Ellison and run by Antech Diagnostic Laboratories, tests for antibodies to one specific protein of S. neurona (SAG-1). This test reports a quantitative result.

The advantage of these newer tests is that they do provide some idea of how high a titer or response the individual horse is making. A horse with a high titer and clinical signs of EPM is much more likely to actually have the disease.

The disadvantage of these tests is that they have not been in use long enough or used on enough horses to accurately evaluate their merits. More testing on larger numbers of horses is needed to show that these tests are indeed selective and specific enough to be consistent with or even better than the tests currently available.

An additional complication is the fact that we now know that there are SAG-1 + and SAG-1- strains of S. neurona. It is not yet known whether these SAG-5+ strains, which are SAG-1-, will cross-react on tests developed using SAG-1+ antigen or if these tests can identify a SAG-5+ infected horse. It is also unclear as to what percentage of EPM affected horses are infected with SAG-1+ or SAG-5+ strains.

Additional work must now be done in this area to clarify these concerns.

If the SAG-1+ vs. SAG-5+ issue can be resolved accurately, then these tests would fit nicely into the suggested work-up that is the best way for veterinarians to diagnose EPM infection in the horse.

"A complete history and thorough physical exam is absolutely critical," Witonsky says.

"It is important to have a complete list of differential diagnoses, considering signalment, clinical signs, vaccination history, localization of neurological signs and sometimes multiple diagnostic tests to rule in and rule out other causes of neurological disease."

All of this information, evaluations about disease progression and re-examination when necessary, and a positive "high" serum titer, especially a quantitative newer test titer (as opposed to the qualitative western blot test) showing "active" infection, may make EPM just a little bit easier to diagnose definitively.

Marcella is an equine practitioner in Canton, Ga.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.