Canine and feline urolith epidemiology: 1981-2013

A look at the trends seen over the past three decadesand what it could mean for veterinary patients in the future.

The mineral composition of canine and feline uroliths has changed in the past three decades. In the early 1980s, calcium oxalate uroliths were considered to be rare in dogs and cats, while struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) was the most common mineral type (Figures 1 and 2). In this article, we evaluate canine and feline urolith submissions to the Minnesota Urolith Center (MUC) to determine if trends observed in 2013 were different from previous years. We then look at what this information might mean for our patients in the future.

Figure 1

Figure 2

A comparison of uroliths over three decades

Overall, data indicate minimal variation in calcium oxalate urolith percentages during the most recent decade. But looking over a greater period of time, a major shift in composition has occurred. In the past 33 years, there has been a substantial increase in calcium oxalate uroliths and a substantial decrease in struvite uroliths observed in dogs and cats (Figures 1, 2, 7 and 8).

Figure 7

Figure 8

In 1981, calcium oxalate formed 5 percent of canine and 1.5 percent of feline uroliths. Beginning in 1986, we observed a decline in the percentage of feline struvite uroliths and a reciprocal increase in calcium oxalate uroliths. By 1993, feline calcium oxalate had become the predominant mineral type.

Most recently, feline struvite and calcium oxalate have remained fairly comparable. In 2013, struvite represented 46 percent and calcium oxalate represented 41 percent of feline uroliths submitted to the MUC (Figure 3).

A similar but more gradual change was noted in canine uroliths. By 2002, calcium oxalate had overtaken struvite as the predominant mineral type. Since that time, the prevalence of struvite and calcium oxalate uroliths has remained fairly constant.

In 2013, struvite represented 38 percent and calcium oxalate represented 42 percent of canine uroliths submitted to the MUC (Figure 4).

Possible causes of this decline in the frequency of struvite uroliths and a reciprocal increase in calcium oxalate uroliths include:

- Widespread use of a calculolytic food to dissolve struvite uroliths

- Widespread use of maintenance and preventive foods modified to minimize struvite crystalluria (some dietary risk factors that decrease the risk of struvite uroliths increase the risk of calcium oxalate uroliths)

- Inconsistent follow-up evaluation with urinalysis and radiography to determine the efficacy of dietary management protocols.

Figures 3 and 4

Therapeutic implications

Be aware that infection-induced struvite is a major mineral type in dogs, and sterile struvite is a predominant mineral type in cats. The causes of sterile and infection-induced struvite are different. This difference is essential to consider when formulating therapeutic plans.

Because struvite is the predominant mineral type, its important to consider a struvitolytic diet to manage cats at risk for struvite urolithiasis. Currently, therapeutic diets are available that promote struvite urolith dissolution in a short period. In a double-blind study, a therapeutic diet (Prescription Diet c/d Multicare FelineHills Pet Nutrition) performed as expected in the dissolution of sterile struvite uroliths (Figures 5 and 6).1

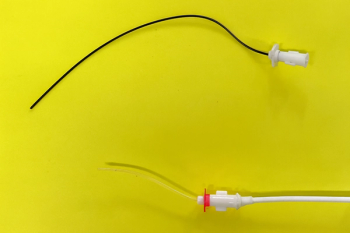

Figure 5

Figure 6

However, not all urolith types can be dissolved with dietary manipulation. Those uroliths that have not shown evidence of dissolution in three to four weeks (provided the owner is compliant with feeding instructions) should be removed and sent to a reputable laboratory for evaluation of mineral composition.

Minimizing recurrence of almost all struvite uroliths in dogs requires treating and preventing urinary tract infections. This is because more than 90 percent of canine struvite stones are infection-induced.2

The role of low magnesium and phosphorus therapeutic foods that acidify the urine have not been evaluated in their ability to minimize recurrence of infection-induced struvite stones, but dietary therapy should be considered secondary to controlling urinary tract infection.

A diet to dissolve calcium oxalate uroliths is not available. Formation of calcium oxalate uroliths is associated with a complex and incompletely understood sequence of events. It is accepted that initial crystal formation and subsequent crystal growth are at least partly a reflection of urine supersaturation. Therefore, controlling the risk factors promoting urine calcium oxalate supersaturation (e.g., hypercalciuria, hyperoxaluria, hyperaciduria, hypocitraturia and highly concentrated urine) should minimize calcium oxalate urolith recurrence in dogs and cats.

High-moisture foods designed to promote less acidic urine are currently available on the market and help minimize dietary risk factors for calcium oxalate urolithiasis

Other mineral types

Purine (including uric acid, ammonium urate and other salts of uric acid) is the third most common mineral type in dogs and cats. Four percent of canine and 5 percent of feline uroliths in 2013 were composed of purine.

Risk factors promoting urine urate supersaturation and subsequent purine urolith formation include hyperuricosuria (as seen in Dalmatians, dogs with hepatic portosystemic shunts, breeds carrying the gene for hyperuricosuria and some dogs receiving chemotherapy), acidic urine and highly concentrated urine. In many cats, an underlying cause has not yet been determined.

Compound uroliths

We consider uroliths composed of two different mineral types in separate layers within the same urolith to be compound. Compound uroliths represented 5 percent of feline uroliths and 10 percent of canine uroliths received at the MUC in 2013. Therapeutically, this highlights the importance of quantitative analysis.

Although some uroliths have a characteristic gross appearance or habit, it is only by sectioning the urolith and performing quantitative analysis on all areas of the stone that an accurate patient management strategy can be determined. In most cases, preventive therapy addressing the mineral comprising the interior of the urolith should be considered.

A continuing trend

On a side note, during the past 30 years, the number of canine urolith submissions has far exceeded the number of feline urolith submissions. For example, in 2013 we received 66,310 canine uroliths and 15,602 feline uroliths. This results in a ratio of 4.25 canine uroliths for every feline urolith we received. This continuing trend is surprising given that there are more cats than dogs living with families in the United States.3

Authors note: With continuing support from Hills Pet Nutrition, as well as contributions from veterinarians and pet owners worldwide, the Minnesota Urolith Center is able to provide complimentary quantitative urolith analysis. Online submission, email notification and electronic retrieval of results are available. With access to our database of about 900,000 samples, the veterinary community is provided with the latest information on urolith trends, treatment and prevention suggestions. For details, visit

References

1. Lulich JP, Kruger JM, Macleay JM, et al. Efficacy of two commercially available, low-magnesium, urine-acidifying dry foods for the dissolution of struvite uroliths in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2013;243:1147-1153.

2. Osborne CA, Lulich JP, Polzin DJ, et al. Medical dissolution and prevention of canine struvite urolithiasis. Twenty years of experience. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1999;29:73-111.

3. American Veterinary Medical Association. U.S. pet ownership and demographic sourcebook. 2012

Dr. Osborne and Dr. Lulich are co-directors of the Minnesota Urolith Center. Dr. Nwaokorie is a post-doctoral associate in the Veterinary Clinical Sciences Department at the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Minnesota. Dr. Hunprasit is a PhD candidate in the Veterinary Clinical Sciences Department at the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Minnesota.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.