Your stallion infected my mare: Hmmm, really??? (Proceedings)

The significance of venereally transmitted disease in horses is gaining importance since the number of mares being bred by a single stallion has increased significantly.

The significance of venereally transmitted disease in horses is gaining importance since the number of mares being bred by a single stallion has increased significantly. Thoroughbred stallions often breed 100 or more mares by natural cover while stallions registered in an associations that allow artificial insemination can breed upwards of 200 mares in a single single. Furthermore, with the acceptance of frozen semen virtually any country can spread disease in a country or continent far removed from the stallion's direct area of influence.

The objective of this paper is to describe the most important potential diseases that can be transmitted by the stallion by direct genital contact or through its semen. Management measures as well as some of the risk factors that would increase or reduce the venereal transmission of disease are discussed.

The risk factors that may increase the chances of disease transmission through semen. 1) Natural Mating, 2) Poor Stallion Management, 3) Inconsistent Breeding Method and 4) Artificial Insemination.

Direct sexual contact perhaps poses the biggest risk for venereally transmitted disease. All mares but particularly those with poor fertility histories should be cultured prior to breeding. On the other hand stallions breeding by natural cover should be monitored on a regular basis.

Unfortunately stallions that are not stood at a breeding farm tend to have lower numbers of mares per season and poorer reproductive management. Hygienic procedures in these cases are often neglected and these stallions or mares can be carriers of different microorganisms. In addition often these horses are poorly housed which can contribute to colonization of the penis by certain bacteria.

In breeds that allow AI, it is not uncommon for stallion to breed several mares by natural cover at the farm, under no veterinary supervision. However often times the owner will request for the stallion to be collected so semen can be shipped to other mares. These inconsistent practices can increase the risk of a stallion getting contaminated or of spreading microorganisms to several mares.

AI has been advocated as a technique that greatly reduces the risk of disease transmission. Stallions breeding artificially could breed over 200 mares during the year. In general these horses have been carefully scrutinized for venereal diseases and as housed with other animals of similar health status. However other factors such as the hygiene of the artificial vaginal, lubricants, collection bottles, dummy mount, or teaser mare and semen packing material could serve as sources of bacterial contamination of venereal disease transmission. However if some of these factors are overlooked, they can, instead serve as a multiplier of disease.

Bacteria, Virus and Protozoa are the microbiological agents that can be transmitted through semen, cause diseases and affect fertility. In addition genetic diseases are important to keep In mind when breeding horses.

Bacteria

The stallion can harbor bacteria in the external genitalia as well as in the internal genital organs. Except when only the sperm rich fraction is collected with an open artificial vagina, virtually every stallion and all ejaculates have contaminants that could be potential pathogens in the mare. The bacteria that constitute the normal flora of the stallion's penis rarely produce genital infections in reproductively sound mares. It is not uncommon to culture an unwashed stallion penis or fossa glandis and harvest a milieu of bacteria including; Escherichia coli, Sterptococcus zooepidemicus, Streptococcus equsimilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus spp, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomona aureginosa. However, when the normal bacterial flora is a disrupted, potentially pathogenic bacterium particularly, Pseudomonas aureginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae can colonize the penis and prepuce. These organisms rarely produce clinical disease in stallions, but can be transmitted to the mare's genital tract at the time of breeding, resulting in infectious endometritis and associated subfertility. The factors that contribute to the colonization of the penis by these are not clearly determined. Some believe that the normal bacterial microflora of the stallion's external genitalia possibly combats proliferation of pathogens. However the frequent washing of the penis, with detergents or disinfectants could removes these non-pathogenic resident bacteria, increasing the susceptibility of the penis and prepuce to colonization by pathogenic organisms. Others dispute this concept, asserting that repeated washing of the external genitalia alone does not contribute to overgrowth of pathogenic microorganisms. The environment in which a stallion is housed may influence the type of organisms harbored on the external genitalia. These organisms can also be acquired at the time of breeding from a mare with a genital infection.

A sudden and unexplained drop in pregnancy rates should warn the stallion manager about a possible stallion genital infection. Diagnosis of the colonization of the stallion's penis by a pathogen is done by careful evaluation of breeding records and early pregnancy diagnosis. Definitive diagnosis is done by isolation of the microorganism in culture. In addition isolation of the same microorganism with a similar sensitivity pattern from the non-pregnant mares will help confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment of penile colonization depends on the type of bacteria. And method of breeding. For stallions breeding by AI a thorough penile wash prior to semen collection is recommended. The filtered semen is then diluted with extender containing antibiotic for which the bacterial is sensitive. Incubation should be done for at least 30 min. prior to insemination. Stallions breeding by natural cover should be washed and scrubbed thoroughly. After washing the penis is dried. The mare is covered and then a uterine lavage is performed infusing the mare with appropriate antibiotic between 4 and 6 hrs post breeding.

Stallions with penile colonization by Klebsiella or Pseudomonas can be washed with a weak solution of HCl or sodium hypochlorite. Systemic antibiotic treatment should be avoided since it has proved unrewarding in most cases.

Contagious equine metritis

Contagious equine metritis (CEM) caused by the cocco-bacillus Taylorella equigenitalis is perhaps the only true venereal sexually transmissible disease in horses. CEM although not present in North America, could be close to being "imported" particularly through frozen semen from untested stallions.

CEM infected stallions are asymptomatic carriers and harbor the organism in the urethral fossa, the urethra or the sheath. Mares bred to infected stallions will develop a severe purulent vaginitis, cervicitis and endometritis. These mares will appear to clean up but will remain infected with and the organism can be cultured from the clitoral fossa or clitoral sinuses. Diagnosis of CEM is done by culturing the organism. Aimes charcoal supplemented medium is recommended for transport. Swabs are plated on Columbia blood-chocolate agar at 37 degrees C and 7% carbon dioxide. Because of the slow growth of T. equigenitalis the possibility of false negative results is relatively high.

A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay, appears to be sensitive with initial results indicating an unexpected high incidence of the agent in horses. In a study, randomly selected mares with no clinical signs of CEM were sampled and all were negative for Taylorella equigenitalis in conventional culture, but 49% were positive for Taylorella-DNA in the PCR-assay. Positives were found in all breeds tested, even horses imported from the isolated population in Iceland. The high incidence of CEM in the horse population, apparently without clinical signs, the occurrence of incidental clinical cases and the known variation between strains indicate that Taylorella is endemic in the horse population and Taylorella equigenitalis must have been present long before it was first isolated in 1977. The fertility of 6 positive stallions by culture used in an AI-program was not affected during the carrier period; also foaling rates of these stallions were not affected. Even a cultured positive stallion breeding by natural cover showed normal fertility results. This suggests that the significance of Taylorella in breeding may be limited and regulations can be adapted to the new findings. Validation of this assay to reduce the level of false positive will be very advantageous.

Internal bacterial infections

Bacterial infections of the accessory genital glands, epididymides, or testes are uncommon in stallions, but are clinically important because of their persistent nature, tendency for venereal transmission, and detrimental effect on fertility of stallions. These infected stallions are usually identified initially by the presence of numerous neutrophils in ejaculates, while other diagnostic procedures such as ultrasound and endoscopy are used to localize the site of infection. Treatment is generally done by combining local and systemic therapy.

Viral

Although many viruses can affect the stallion's reproductive performance, only two are considered as venereally transmissible. Equine Herpes virus III, the etiologic agent for equine coital exanthema and equine arteritis virus (EAV) responsible for equine viral arteritis (EVA).

Equine coital exanthema

Equine coital exanthema caused by herpes virus III and can be transmitted from male to female or vice versa. It is characterized by the formation of small (0.5-1 cm) blister-like lesions on the penis and prepuce or on the vulvar and perineal area of the mare. These lesions will eventually break to form skin ulcers that usually resolve completely in 3-4 weeks leaving some round white scars in the affected area. In some instances mild fever and slight depression can be observed. Although the effect on fertility is not known, mares and stallions should be sexually rested during the acute phase of the disease to avoid further spread.

Equine viral arteritis

Equine arteritis virus (EAV) is a small RNA virus that can infect horses and donkeys, is thought to be present in most countries that have serosurveillance except for Iceland and Japan. Presently EAV is responsible for major restrictions in the international movement of horses and semen. While the majority of EAV infections are a symptomatic, acutely infected animals may develop a wide range of clinical signs, including fever, limb and ventral edema, depression, rhinitis, and conjunctivitis. The virus may cause abortion and has caused mortality in neonates. After natural EAV infection, most horses develop a solid, long-term immunity to disease. Mares and geldings eliminate virus within 60 days, but 30 to 60% of acutely infected stallions will become persistently infected, which will maintain EAV within the reproductive tract, permanently shed and potentially transmit the virus through the semen. Mares infected venereally may not have clinical signs, but normally will shed large amounts of virus in nasopharyngeal secretions and in urine which may result in the lateral spread of infection by an aerosol route.

The consequence of venereally acquired arteritis virus is minimal, with no known effects on conception rate. However when pregnant mares are infected abortions may occur regardless of gestation length.

Identification of carrier stallions is crucial to control the dissemination of EAV. These animals can be identified by serological screening using a virus neutralization (VN) test. If positive at a titer of 1:4 the stallion should be tested for persistent infection by virus isolation from the sperm-rich fraction of the ejaculate. An alternative to virus isolation is the test for seroconversion of seronegative mares mated by natural cover with the suspected stallion. Shedding stallions should not be used for breeding, or should be bred only to mares that had been previously exposed to the virus either by vaccination or natural exposure. Mares that are vaccinated, bred to shedding stallions or bred with infected semen should be isolated from seronegative animals for three weeks after treatment or exposure.

One of the greatest risks of EAV infection is abortion, which may occur even if the mare had no clinical signs. In cases of natural exposure, the abortion rate has varied from less than 10% to more than 60% and can occur between 3 and 10 months of gestation. The abortions appear to result from the direct impairment of maternal-fetal support and not from fetal infection.

While mares and geldings are able to eliminate virus from all body tissues by 60 days post infection 30 to 60 % of stallions become persistently infected. In these animals, virus is maintained in the accessory organs of the reproductive tract, principally the ampullae of the vas deferens and is shed constantly in the semen. There are three possible carrier states that could develop in a stallion exposed to the arteritis virus. A) A short-term state during convalescence (duration of several weeks), B) A medium-term carrier state (lasting for 3 to 9 months), and C) A long-term chronic condition, which may persist for years after the initial infection. The development and maintenance of virus persistence is, in large part, dependent of the presence of testosterone. Persistently infected stallions when castrated but supplemented with exogenous testosterone continue to shed virus, while those administered a placebo ceased virus shedding shortly after castration. In addition, virus could not be detected in geldings after day 60-post infection. The ability of a large percentage of stallions to effectively eliminate the virus in time suggests that differences in the immune response of the host may be involved, or alternatively, virus strains may have biological differences, which influence their ability to persist in the reproductive tract. Establishment of persistence may involve a multifactorial process, with dependence on both host and viral factors.

After clinical recovery from initial infection, there is no significant decrease in the fertility of shedding stallions. Mares infected after service by a carrier stallion do not appear to have any related fertility problems during the same or subsequent years and there are no reports of mares becoming EAV carriers or chronic shedders, nor of virus passage by the venereal route from a seropositive mare causing clinical disease or seroconversion in a stallion.

The two major routes by which EAV is spread are: aerosols generated from secretions (respiratory or urine) from acutely infected animals or from secretions from recent abortions; and venereal from semen from a shedding stallion. Since personnel and fomites play a minor role in virus dissemination, close contact between animals is generally required for efficient spread of the virus from one animal to another. Virus is also viable in fresh, chilled, and frozen semen, and venereal transmission is efficient, with 85 to 100 % of seronegative mares seroconverting after being bred to stallions shedding virus. In several cases, outbreaks of clinical disease have been traced to a persistently infected stallion.

Clinically EVA resembles several other viral infections of equines and a definitive diagnosis requires laboratory confirmation. Acute infections can be diagnosed by virus isolation or by serologically identifying a 4-fold or greater rise in neutralizing titer between acute and convalescent serum samples. In the case of abortion, virus isolation can be attempted from fetal and placental tissues or seroconversion can be demonstrated in the mare. Persistent infection in stallions can be diagnosed by first screening serum for antibody in a serum neutralization (SN) test. If seropositive at a titer of 1:4, virus isolation should be performed on the untreated, sperm-rich fraction of the ejaculate or the stallion should be test mated to seronegative mares who are monitored for seroconversion.

Serum neutralization test (SN) is the method of choice for antibody detection. Detectable antibody titers develop 2 to 4 weeks following infection, are maximal at 2 to 4 months, and remain stable for several years. A titer of 1:4 or greater in duplicate sera is considered EAV seropositive. Semen from seropositive stallions must be tested to determine the stallion's EVA status as a carries.

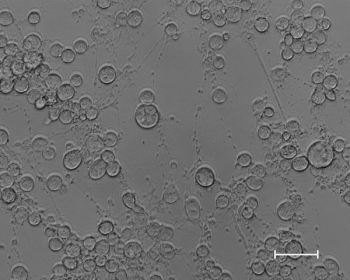

The current test for virus identification in tissues and semen is to isolate the virus in monolayers of rabitt kidney (RK-13) cell cultures and observe its cytopathic effect. The virus can be positively identified by immunofluorescence or immunocytochemistry using specific polyclonal or monoclonal antisera or by testing in a virus neutralization assay with defined reference antisera. To have a proper sample for virus isolation it is important that the samples be collected, processed and shipped in a proper way.

To determine the shedding status, seropositive stallions at a titer of 1:4 in a SN test, a semen sample should be collected using an artificial vagina or a condom and a phantom or a teaser mare. If this is not possible, a dismount sample can be collected at the time of breeding, however this is less satisfactory. The sample should be from the sperm-rich fraction of the full ejaculate and should be chilled immediately and shipped at 4 C to arrive at the diagnostic facility within 24 hours. If this is not possible, the sample should be frozen at -20 C and shipped to the diagnostic facility under these conditions. Submission of two samples, collected the same day or on consecutive days is recommended. Washing of the penis with antiseptics or disinfectants prior to collection of the samples should be avoided. Samples of commercial frozen semen could also be tested but it is necessary to have at least 2 billion sperm cells for the sample to be representative. False negatives have been reported due to the lack of seminal plasma in cryopreserved semen.

Suspected abortions from EAV infection can be diagnosed with the submission of several samples to an appropriate laboratory. These samples include, both fetal and placental tissues that normally contain large amounts of viral particles. Placental and fetal fluids as well as fetal spleen, lung, and kidney should be collected in a sterile manner as soon as possible after the abortion occurs, chilled on ice, and submitted for virus isolation. Blood should be obtained from the mare at the time of the abortion and three weeks later for testing by SN.

Prevention and control

Modified live (ARVAC-Fort Dodge) and a formalin-inactivated (ARTERVAC) vaccines are currently available. Both vaccines induce virus-neutralizing antibodies, the presence of which correlates with protection from disease, abortion, and the development of persistent infection. EAV, as discussed before, has a worldwide distribution and its prevalence is increasing. As a consequence, an increasing number of equine viral arteritis (EVA) outbreaks are being reported. This trend is likely to continue unless action is taken to slow or halt the transmission of this agent through semen.

The MLV, modified live vaccine, (ARVAC) does not produce any side effects in vaccinated stallions apart from a possible short term abnormality of sperm morphology, and a mild fever with no overt clinical signs. However, live virus can be isolated sporadically from the nasopharynx and blood after MLV vaccination. SN antibody titers are induced within 5 to 8 days and persist for at least 2 years.

The MLV protects against clinical disease and reduces the amount of virus shed from the respiratory tract in experimental infection. Mares served by vaccinated stallions are not infected by EAV and vaccinated mares experimentally challenged by artificial insemination are protected from clinical disease, but not infection. In the field the MLV vaccine has been used to control EAV outbreaks in some states of the USA since 1984 but the vaccine is not licensed worldwide.

EVA is entirely preventable if simple serosurveillance and hygiene procedures are followed by horse owners, breeders, and barn managers. Controlling the dissemination of EAV requires a concerted effort on the part of all those involved in the equine industry. Current international regulations have made all of us that EVA is endemic, present in all breeds of horses and in almost every country and therefore it should not be ignored. The presence of neutralizing antibody that correlates well with protection from disease, abortion, and the development of persistent infection in stallions is evidence that control programs, once instituted, have been successful.

Protozoal

Trypanosoma equiperdum is the etiologic agent for Dourine or Mal du Coit. The organism is not present in the US or Europe but it is still endemic in Africa, some areas in Asia and South America. It is perhaps the only protozoal organism that can be transmitted venereally. Tentative diagnosis is made by the clinical manifestation of the disease, which includes intermittent fever, depression, progressive loss of body condition and severe purulent discharge from the urethra. Definitive diagnosis is performed by complement fixation and culture.

Other microorganisms

Other microorganisms that can be potentially be transmitted venereally include Chlamydia spp. and Micoplasma spp. Although both of these organisms have been isolated from the urethra of stallions, their effect on equine fertility is not well known. However it is important to be aware of the possibility of these agents causing infertility both in mares and stallions. Candida spp and Aspergillus spp. Although not commonly present in semen or the genital tract of the stallion can be potential pathogens particularly in artificial insemination programs where the hygiene of the collection and processing equipment is not well monitored.

Genetic diseases

One of the main reasons for stallions standing at stud is to pass on to their offspring their genetic attributes. However sometimes stallions can be carriers of a hereditary condition that when mated to certain mares could be expressed in his foals. Perhaps the clearest example of the potential effect of the genetic impact is the "Impressive syndrome" of the quarter horses. Where thousands of mares where bred by one stallion transmitting the HYPP gene.

Conditions such as genetic mosaics (63 XO/64 XY or 65 XYY), certain sperm defects such as detached heads or mid piece defects and testicular characteristics such as small testicular size or premature testicular degeneration are or could potentially be transmitted genetically.

Other conditions that could also have a hereditary basis include CID in Arabians, umbilical and scrotal hernias, parrot mouth, cryptorchidism, testicular rotation and others.

The expression of any of these genetic traits can have profound and devastating effects on a breeding program. When a condition is suspected it is important that cytogenetic or molecular diagnosis be used to identify undesirable traits that will be express in the adult animal.

Conclusion

The pivotal point in prevention and control of disease is the identification of infected stallions and mares, and the institution of management procedures to prevent the further spread of any disease to susceptible populations through the breeding of mares by natural service or artificial insemination. If a stallion proves to be a carrier, he should either not be used for breeding through natural service or his semen should be treated with proper antibiotics in cases of bacterial disease. In the case of EVA, stallions might still be used provided that the mare owners are informed that the stallion is shedders so that they can take the preventive measurements i.e. vaccinate the mares.

The option to use a particular stallion in a breeding facility may depend on the value of the stallion as a breeding animal and individual regional regulations. Whatever the case may be all stallions should have a diagnosed status prior to each breeding season.

Breeding managers and/or stallion owners must be aware that poor genital hygiene of a breeding stallion and of the mares at the time of breeding will greatly increase the chances of spreading disease form a stallion to a group of mares or from a mare to a stallion. Poor management reflected on poor breeding records, and poor hygiene at the time of breeding are perhaps the most common reasons for having venereal diseases cause severe and irreversible problems on the fertility of any breeding operation.

References

1. Glazer AL et al. (1997) Equine Arteritis Virus. Theriogenology 47;1275-1295.

2. Parlevliet JM and Samper JC. (2000) Disease Transmission Through Semen. In: Equine Breeding Management and Artificial Insemination. Samper JC ed. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia.

3. Timoney PJ. (1998) Aspects of the Occurrence, Diagnosis and Control of Selected Venereal Diseases of the Stallion. Proccedings of Stallion Reproduction Symposium, Society for Theriogenology. Baltimore. MD pp. 76-83.

4. Varner DD. (1998) External and Internal Genital Infections if Stallions. Proceedings of Stallion Reproduction Symposium, Society for Theriogenology. Baltimore. MD pp. 84-94.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.