- dvm360 December 2021

- Volume 52

Urolithiasis and the impact of nutritional management

Dogs and cats can develop several different types of uroliths.

Urolithiasis is the formation of stones in the urinary tract of cats and dogs that is caused by supersaturation of the urine with various types of minerals and organic materials.1 Urolithiasis is common in both species and can lead to stranguria, hematuria, pollakiuria, urinary obstruction, and, in severe cases, death due to electrolyte and metabolic abnormalities.2

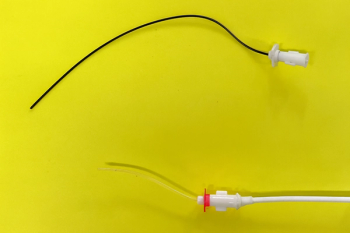

Urinary stones can occur anywhere in the urinary tract but the bladder and urethra are the most common locations in both cats and dogs.3,4 After a thorough history and physical exam, diagnostics such as a complete blood count, serum biochemistry, urinalysis, and imaging are used to determine the presence of possible underlying disease within the urinary tract. In many cases, crystalluria may be incidental on urinalysis but this does not mean there is an immediate risk of urinary stones.5 In other cases, a patient may present in critical condition necessitating stabilization, urinary catheter placement, correction of metabolic derangements (azotemia, hyperkalemia, etc), and cardiac arrhythmia. Following stabilization, surgical or endoscopic intervention may be pursued via cystotomy or cystoscopy with lithotripsy.

Risk factors for urolithiasis

Several factors are required for crystal formation, including urine pH, mineral concentration, and presence or absence of promoters or inhibitors. Relative supersaturation (RSS) is a way to assist in determining the risk for crystal formation and is calculated by using urine pH and concentration of lithogenic (stone-producing) substances in the urine. An RSS less than 1 indicates undersaturation and minimal risk of crystal formation, but an RSS greater than 1 indicates supersaturation and an increased risk of crystal and stone formation.5 RSS is not available for clinical use, so clinicians must indirectly assess a patient’s risk for urolithiasis by evaluating urine pH, urine specific gravity, and microscopic evaluation of urine.

Dogs and cats can develop different types of uroliths: calcium oxalate (CaOx), struvite, urate, cysteine, and silica. Results from recent studies show that struvites are the most common uroliths seen in cats (47.1%) and CaOx are the most common uroliths in dogs (47%).3,4 Risk factors for urolithiasis depend on the stone composition and include age, sex, breed, presence of urinary tract infection (UTI), diet, metabolic abnormalities, and genetics.

Risk factors for common uroliths affecting cats and dogs are as follows:

- CaOx stones are composed of CaOx monohydrate and dihydrate. This type of stone is most common in older (> 7 years), male neutered cats, and dogs with acidic urine. Cat breeds such as the Burmese and Persian and dogs such as the poodle, Pomeranian, Lhasa apso, and Maltese have been found to be at a higher risk for CaOx stones. Underlying hypercalcemia is present in approximately 35% of cats with CaOx.5

- Struvite stones are composed of magnesium, ammonium, and phosphate. In cats, middle-aged to older (4-10 years) females tend to develop these stones in sterile, alkaline urine. Cat breeds found to have a higher risk are the exotic shorthair, Ragdoll, and Himalayan. In dogs, struvite stones also occur mostly in females with alkaline urine, but dogs tend to be younger (66% are < 4 years old) and approximately 76% of struvites are associated with UTIs with urease-producing bacteria such as Staphylococcus species (spp) and Proteus spp. At-risk breeds include Labradors, cocker and springer spaniels, bichons, and shih tzus.1,4,5

- Urate stones occur more commonly in dogs and are less common in cats. These stones are made from uric acid and occur secondary to portosystemic shunts (cats and dogs) and a genetic mutation (dogs), SLC2A9 mutation, resulting in abnormal purine breakdown. Urate stones occur in young to middle-aged cats and dogs, with intact female dogs having an increased occurrence. These radiolucent stones are commonly found in acidic urine and are commonly seen in the dalmatian, English bulldog, and pit bull breeds.3,5

- Two rare uroliths are cysteine and silica. These radiolucent stones are rarely seen in cats but are associated with acidic urine and are caused by renal transport dysfunction (cysteine). In dogs, young to middle-aged intact males are more commonly seen with cysteine stones, whereas older neutered males and intact females are seen with silica uroliths.5

In general, the goals of nutritional management are to dissolve stones when possible and to minimize the recurrence of stone reformation. Depending on the stone’s composition, various strategies must be employed to achieve these goals.

Urine dilution is a key strategy for the dissolution and prevention of stones. This is accomplished by increased water intake leading to diuresis, which decreases the concentration of crystal precursors and the time for crystal formation. Increasing water intake can be accomplished by feeding canned diets with greater than 70% moisture or by adding water to dry kibble in a 1.5:1 ratio (~ 80% moisture). Additionally, limiting the concentration of dietary precursors (protein, minerals, etc) and altering urine pH are needed to maximize the effect of therapeutic diets. Below is an overview of dietary causes, strategies, and goals for treating cats and dogs with the different types of uroliths.1

Calcium oxalate

In cats and dogs, acidic urine (pH, < 6.25), increased dietary intake of Ca, hypercalcemia, and metabolic acidosis are factors leading to the formation of CaOx stones; acidemia releases Ca and phosphate from bone and decreases citrate, an inhibitor of CaOx crystals, which further adds to an increased Ca concentration. To combat these dietary and metabolic factors, dietary strategies such as increasing dietary moisture and protein content along with certain minerals (sodium and potassium) and those aimed at producing moderately acidic urine should be employed. The goal of dietary management is to decrease the risk of recurrence after surgical intervention or to slow the growth of nonsurgical uroliths, as CaOx stones are not amenable to dissolution; in cats, the recurrence rate is approximately 33%, whereas stones recur in up to 57% of cases for dogs.1

Struvite

Cats and dogs can both develop struvite stones, but the factors leading to these stones are different. Cats develop struvite stones in response to increased dietary intake of phosphorus and magnesium, and dogs tend to develop these stones due to alkaline urine, which increases the availability of phosphorus to form struvites. In dogs, these stones are most commonly secondary to UTIs. In both species, diet strategies include urine dilution to decrease concentration, the production of acidic urine pH (< 6.2), and feeding multiple small meals to avoid the postprandial alkaline tide from 1 to 2 large meals. The goals of these diets are to produce a urine pH of 6.0 to 6.3 and decease urine specific gravity to less than 1.030 in cats and less than 1.020 in dogs. Struvite stones are amenable to dissolution and nutritional management can be indicated prior to surgery. In cats, dissolution can take around 30 days (range, 6-141 days) depending on diet and urolith size, whereas in dogs it may take up to 3 months of nutritional management in addition to antibiotic therapy. Despite nutritional management, recurrence is seen in up to 7% of cats and 21% of dogs.1,2,5,6

Urates

Urate stones are seen with abnormal purine metabolism, which can be found in organ meat. These stones are most often seen with portosystemic shunts, and a genetic mutation (SLC2A9) in some dogs. Dietary strategies include increased moisture intake, alkalizing the urine, and protein-restricted or liver diets. The goal of nutritional intervention is to attempt dissolution and prevent recurrence in susceptible cats and dogs. Recurrence is seen in up to 13% of cats and 33% of dogs.1,2

Cysteine and silica stones are uncommon, but diets use the same strategies of increased water intake, limiting intake of predisposing factors, and alkalizing the urine to prevent recurrence.

Overall, the success of dietary management of any urolith is proper identification, managing any underlying causes (diet, anatomic, metabolic, etc), and owner adherence. The core strategies to successfully treat and/or prevent uroliths are promoting water intake, controlling dietary precursors, altering urine pH, and regular monitoring to ensure therapy is successful.

Timothy Ericksen, DVM, is a New Jersey native who received his doctorate in veterinary medicine at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in 2015. Following veterinary school, he completed a rotating internship in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Ericksen began his surgery residency at NorthStar VETS in Robbinsville, New Jersey, in July 2021. His interests include wound management, fracture management, and emergency surgery.

References

- Westropp JL, Ruby AL, Campbell SJ, Ling GV. Canine and feline urolithiasis: pathophysiology, epidemiology and management. In: Bojrab MJ, Monnet E, eds. Mechanisms of Disease in Small Animal Surgery. 3rd ed. Teton NewMedia; 2012:387-391.

- Lipscomb VJ. Bladder. In: Johnston SA, Tobias KM, eds. Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal Expert Consult. Vol. 2. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2018:2219-2233.

- Kopecny L, Palm CA, Segev G, Westropp JL. Urolithiasis in dogs: evaluation of trends in urolith composition and risk factors (2006-2018). J Vet Intern Med. 2021;35(3):1406-1415. doi:10.1111/jvim.16114

- Kopecny L, Palm CA, Segev G, Larsen JA, Westropp JL. Urolithiasis in cats: evaluation of trends in urolith composition and risk factors (2005-2018). J Vet Intern Med. 2021;35(3):1397-1405. doi:10/1111/jvim.16121

- Queau Y. Nutritional management of urolithiasis. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2019;49(2):175-186. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2018.10.004

- Tefft KM, Byron JK, Hostnik ET, Daristotle L, Carmella V, Frantz NZ. Effect of a struvite dissolution diet in cats with naturally occurring struvite urolithiasis. J Feline Med Surg. 2021;23(4):269-277. doi:10.1177/1098612X20942382

Articles in this issue

almost 4 years ago

Veterinary Heroes: General Practitioner winner CPT Kelly Willard, DVMalmost 4 years ago

Veterinary Heroes: Emergency Medicine winner Charity J. Uman, MS, DVMalmost 4 years ago

Veterinary Heroes: Dermatology winner Maria Ierace, DVMalmost 4 years ago

Veterinary Heroes: Client Service Representative winner Susie Martinabout 4 years ago

Handling separation anxiety spikes when life changesabout 4 years ago

From a flicker to a flame: Where's your sense of purpose?about 4 years ago

Benefits of upgrading technology for clinic workflowNewsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.