Seeking answers for skin disease in draft horses

It's a painful, disfiguring disease that may strike horses as early as 2 years of age, then over time cause formation of large nodules that interfere with normal pastern movement, permanent skin ulceration and lameness, eventually leading to the animals' early demise.

It's a painful, disfiguring disease that may strike horses as early as 2 years of age, then over time cause formation of large nodules that interfere with normal pastern movement, permanent skin ulceration and lameness, eventually leading to the animals' early demise.

Photo 1: A moderate to severe case of chronic progressive lymphedema, with swelling of the leg and formation of pastern folds and numerous skin nodules that are eroded. (PHOTOS: COURTESY OF DR. VERENA AFFOLTER)

The disease is chronic progressive lymphedema (CPL), and it affects large draft breeds with heavily feathered lower extremities. Early on, the disease may appear to be what often is referred to as a therapy-resistant pastern dermatitis, "scratches" or "mud fever," but over time, in addition to skin lesions typical for scratches, affected horses have vascular and lymphatic-vessel changes.

That was found during skin-lesion biopsies submitted to the dermato-pathology service at the University of California-Davis, as reported by Verena Affolter, DVM, PhD, Dipl. ACVP, a professor of dermatopathology, Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology at UC-Davis' School of Veterinary Medicine, in "The Horse Report," published by the school's Center for Equine Health (Vol. 19, No. 4, October 2001).

"The progressive disease is characterized by progressive swelling, fibrosis, marked hyperkeratosis and formation of skin nodules of the distal limbs," says Hilde DeCock, DVM, formerly Affolter's colleague in the same department and now working and teaching in Belgium.

Photo 2: This is a more severe form of CPL with marked swelling and oozing of the skin surface. The partially regrown feathering is covering some of the nodules.

The disease is seen in primarily in Shires, Clydesdales and Belgian draft horses, while other draft breeds are not affected, and certain genetic lines are more readily prone to develop clinical signs, indicating at least a partial genetic etiology and a hereditary component, the colleagues explain.

Although CPL is seen around the country and the world in the three draft breeds, only the researchers at UC-Davis and their colleagues in Ghent, Belgium, are conducting ongoing studies.

They are exploring the genetics and control of the disease, seeking a definitive cause and a method to successfully manage afflicted horses.

The genetic studies include evaluation of the elastin gene, which is currently studied in Leuven, Belgium, and the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR-3), which is studied at UC-Davis by Danika L. Bannasch, DVM, PhD, associate professor in genetics, Department of Population Health and Reproduction. The FOXC2-gene, associated with distichiasis and lymphedema in humans, was evaluated by Bannasch and found to not be associated with equine CPL.

Photo 3: The skin surface has marked hyperkeratosis and the epidermis is markedly thickened, Secondary infections are common, as shown here with an inflammation of the hair-follicle opening.

Presentation, pathology, morphology

Often CPL may go unnoticed by owners until it has progressed significantly to advanced stages. Here is how the UC-Davis Web site describes it: "The earliest lesions are characterized by skin thickening and crusting. Both often are visible only after clipping the long feathering covering the pasterns. Secondary infections develop very easily in these horses' legs and usually consist either of chorioptic mange or bacterial infections. Both dark and white skin on the lower legs is equally affected. These lesions are consistent with pastern dermatitis, a process also seen in other breeds. ... This disease often progresses to include massive secondary infections that produce copious amounts of foul-smelling exudates, generalized illness, debilitation and even death."

Skin lesions typically are milder on the forelimbs and marked to severe on the hind limbs, the UC-Davis group says. The milder forelimb lesions are predominantly restricted to the caudal pastern region and consist of diffuse hyperkeratosis and mild diffuse swelling. The first skin folds often are noticed at 2 years of age. Normal movement is impaired and lameness is seen at about 15 years of age. The more advanced lesions consist of one or two palpably thickened skin folds predominantly in the rear of the pastern region. With progression, the legs become more edematous, the folds bigger and firmer and there is development of nodules, which may become quite large and often are the size of golf balls or even baseballs, Affolter explains. Both skin folds and nodules first develop in the back of the pastern area. With progression, they may extend and encircle the entire lower leg. The nodules become a mechanical problem because they interfere with free movement and exercise.

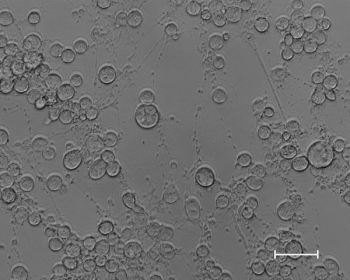

Photo 4: The lymphatic vessels are dilated, and their wall is indistinct and shows edema.

Lymphangiography helps demon-strate the tortuous lymphatics in affected legs, as shown by DeCock, Affolter and colleagues, particularly in the palmar aspect of the metacarpophalangeal joint. Using angiography, a "moderate increase in vascular density can be found in the palmar/plantar soft tissues of affected metacarpalphalangeal joints," the UC-Davis group notes. Lymphoscintigraphy demonstrates that the function of lymphatics is impaired.

Several horses were necropsied at UC-Davis, showing lesions were limited to skin and subcutis of affected legs. Internal organs were within normal limits. In addition to the marked skin lesions with hyperkeratosis, crusting erosion and ulcerations, the legs are markedly enlarged in affected animals, Affolter says.

The subcutaneous tissue contains not only clear fluid, but also firm fibrosis with numerous tortuous lymphatic vessels embedded in the tissue of the pastern region. There are numerous fibrous nodules, which occasionally contain inflammation and abscesses.

Morphological evaluation of skin lesions of Shires, Clydesdales and Belgian draught horses with CPL shows progressive thickening of lymphatic vascular walls associated with chronic dermal edema and fibrosis. By evaluating the tissue by special stains, De Cock, Leen Van Brantegem (DVM, PhD, docent in pathology, Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Antwerp, Belgium) and Affolter demonstrated altered elastin fibers associated with the changes in the lymphatic vessels of the skin.

Photo 5: There are areas of revascularization as an attempt for better perfusion of the fibrotic tissue.

In addition, there is inflammation and neovascularization. Measurements of elastin components, such as desmosin, further illustrates the altered elastin metabolism, which may include diminished production of elastin, production of altered non-functional elastin and associated increased elastin degradation.

In her thesis at the University in Ghent, Belgium, Van Brantegem illustrated higher titers of circulating anti-elastin antibodies in affected horses, which supports the hypothesis that elastin is degraded.

Because severe symptoms do not necessarily present until later in life, CPL-affected younger horses may be bred and therefore pass on the disease before it is diagnosed. It can significantly reduce the lifespan of affected horses. Some Belgian stallions have to be euthanized at 6 to 8 years of age because of progressed CPL. In general, normal movement is impaired and lameness is seen at about 15 years of age.

Disease management

Practitioners are advised to counsel owners of draught breeds to inspect their horses' pasterns below the tufted hair down to the skin around each leg from the tarsal or carpal joint distally, feeling for grape-like bumps and folding lesions, which often are apparent above the line of the pastern feathering.

The feathering not only may somehow potentiate the disease, but mask its presence as well. Regardless of its potential hereditary transmission, it seems draft horses that are kept pastured in very moist/damp/wet conditions and lacking good animal husbandry present with faster disease progression. It might be a good husbandry practice to blow-dry the lower limbs and keep their stall bedding clean and dry.

"The lower-leg swelling is caused by abnormal functioning of the lymphatic system in the skin, which results in chronic lymph edema, fibrosis, a compromised immune system and subsequent secondary infections of the skin. Based on preliminary research, it appears that a similar pathogenic mechanism is involved in the disease that affects these specific draft horse breeds," according to the group at UC-Davis,

"Effective management of the disease is more successful or, in some cases, only successful if the pastern feathering is clipped," but many owners with show horses don't want to clip the feathering, Affolter says.

"The association of poor circulation, decreased lymph drainage, hyperkeratosis and occlusion by dense, long feathering present the perfect environment for opportunistic infections to settle in", and the feathering can interfere with topical treatment and with keeping the pastern region dry," she says.

Other recommendations include keeping the legs of affected horses clean and pristine, treating any infections, providing daily exercise, keeping the horses' legs dry and not leaving the animals outside in rainy weather.

"It seems that wrapping the legs with short-stretch bandages developed for humans with lymphedema has a positive influence on these horses," Affolter says. "The bandaging needs to be done correctly and under professional supervision. It must be padded well and put on with relatively high pressure. There will be a lot of oozing, especially the first week or so, because there is fluid permeating the skin."

DeCock and Van Brantegem wrapped two legs of an affected horse for three months. The result: the swelling, nodular lesions and ulcers diminished.

In a small follow-up study performed on six horses at UC-Davis, the results were not as positive, but those horses' legs were not clipped before the wrapping.

"It has to be emphasized that the bandaging is not a treatment, says Affolter. "As soon as the pressure bandages are no longer applied, the lesions will come back."

Affolter is in contact with people in England who are performing manual lymph drainage, which has been used successfully in horses with more acute lymphedema. It is expected that correct manual lymph drainage would also help keep CPL horses in better health.

The outlook

Equine practitioners and researchers at UC-Davis currently are collecting tissue samples from draft horses with CPL and from older draught horses without the disease to determine the molecular cause of CPL in a genomic-association study to be under way soon. "Ultimately, discovering the gene that causes CPL will help draft-horse breeders eliminate the disease from their breeding programs," says Amy Young, MS, a veterinary researcher at UC-Davis.

"We think CPL is associated with an inappropriate elastic support of the lymphatics," says Affolter. "It is so widespread in the affected breeds that it has to have a genetic background." However, there may be multiple factors involved. "We actually have a hard time finding non-affected draft horses once they are 10 to 12 years of age," Affolter says.

In addition to the work on the hereditary and genetic component, and work on learning how to manage the disease, the UC-Davis group looked at a possible nutritional component to the disease, because various trace nutrients are known to be associated with similar dermatological conditions.

"We have limited data, but we have looked at about 18 horses from a particular farm, and we evaluated zinc, magnesium, vitamin E, selenium and copper levels; they were all within normal limits," Affolter says.

Effect of leg wraps

"It seems that wrapping the legs with short-stretch bandages developed for humans with lymphedema has a positive influence on these horses. The bandaging needs to be done correctly and under professional supervision. It must be padded well and put on with relative high pressure," says Verena Affolter, DVM, PhD, Dipl. ACVP, University of California-Davis

Kane is a Seattle author, researcher and consultant in animal nutrition, physiology and veterinary medicine, with a background in horses, pets and livestock.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.