Investigators are studying Chagas disease with a One Health approach

Chagas disease is being studied by a team of investigators from Texas A&M University in College Station and the University of Georgia (UGA) in Athens. The collaborative team has several new projects that aim to address prevalence, diagnostics, and treatment for the benefit of canines and humans. This work is supported by more than $4 million in funding from the federal government and nongovernmental organizations, according to Texas A&M.1

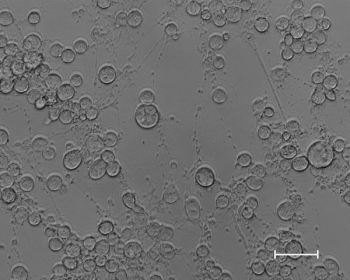

Chagas disease is a tropical condition that is common in dogs and humans and is caused by the Trypanosoma cruzi parasite. The disease is most commonly spread by fecal matter from triatomine insects, which are also known as "kissing bugs" that have bitten and fed on the blood of infected hosts.1

Chagas disease can be life-threatening to both canines and humans when left untreated.2,3 Often unnoticed in early stages, the disease is a chronic infection that can lead to serious heart and digestive system problems. Early diagnosis is important, as the infection is difficult to detect and the disease is challenging to treat, according to Texas A&M.1

“These projects will advance Chagas disease research to understand the process of natural infections, disease, and effect of treatments,” Sarah Hamer, DVM, PhD, MS, DACVPM, a project leader and professor in the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine and Biological Sciences (VMBS), said in a news release.1 “These projects combine many aspects of biomedical research. We’re conducting field and laboratory research, treating dogs, measuring clinical outcomes, and studying ecological factors. It’s truly a ‘One Health’ approach.”

Most human cases of Chagas disease have been reported from South and Central America and Mexico, but there are also established triatomine bug populations across the southern United States, according to Texas A&M. Dogs in Texas are important data sources for Chagas disease because they often encounter these parasites, according to investigators.1

“Unfortunately, Texas has emerged as a hot spot of infected kissing bugs, infected wildlife, and infected dogs across the landscape,” Hamer said.1 “We think dogs are getting infected when they eat the insects.”

RELATED NEWS:

Participants in the study include privately owned canines and working dogs. “Dogs that work in customs and border protection and for the Transportation Security Administration can be exposed to Chagas disease,” Ashley Saunders, DVM, DACVIM, a project leader, professor, and cardiologist in the Department of Small Animal Clinical Studies at Texas A&M VMBS, said in the release. “Some of our work will be a continuation of previous studies of the clinical impacts of the disease on canine cardiac health, as well as how the dogs are exposed to the parasite so we can help minimize their risk.”

While announcing the study initiative and funding, Texas A&M addressed 3 investigation projects included in the research initiative. They include one that may help advance human health through the study of canine patients, another that focuses on working dogs, and a third aiming to improve the management of Chagas disease in canines.1

In the first project, funded by the National Institutes of Health, investigators aim to establish optimal protocols for the detection and treatment of the Chagas infection that can potentially lead to the prevention of cardiac disease development. Innovative diagnostics and treatment strategies are being utilized to conduct this study.1

"There are a number of important questions related to treatment efficacy and the protection that cured subjects have from future infection that cannot be easily addressed in humans but can be in these dog populations that are under intense transmission pressure in Texas,” Rick Tarleton, PhD, a project leader, UGA Regents Professor, and UGA Athletic Association Distinguished Professor, said in a news release.1 This study will track infected individuals using a combination approach with sensitive tests that detect parasite DNA and the body’s response to infection.1

Dogs are a good model for examining the effectiveness of the treatment for humans, as Chagas disease presents similarly in canines as it does in humans. The drug being administered in the study is an existing treatment for Chagas disease in humans, according to Saunders.1

Investigators will monitor working dogs owned by the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in the second project, which is funded by the DHS. These dogs are often trained in areas where Chagas disease is prevalent, including Texas, and investigators are seeking to understand how they are exposed to the disease and the effects it can have on heart health.1

“One of the reasons that monitoring dogs is so helpful is because Chagas disease can produce so many different subsets of health problems,” Saunders said in the release.1 “Some dogs end up with a heart abnormality, but a large number continue living and working happily for many years. Others will die quite suddenly, before anyone knew they had the disease.”

“Recording health information from such a large population of dogs will hopefully help us understand why the disease develops in different ways,” Hamer added.1

Investigators noted that although government-working dogs are commonly trained in Texas, they can perform their jobs anywhere in the US. Therefore, working dogs infected with T cruzi could be transported to regions across the country that do not currently have as much prevalence or awareness of the parasite.

The third project is supported by the American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation. It will develop a staging system for Chagas disease in dogs, with the investigative team treating and monitoring pet dogs brought to Texas A&M’s Small Animal Teaching Hospital.1

“The staging system we develop will help us to categorize the severity of disease, making it easier to determine which dogs will benefit most from drug treatment,” Saunders said.1 “This scoring system will work hand-in-hand with our improved diagnostic and treatment plan.”

References

- Research collaboration takes ‘One Health’ approach to study Chagas disease exposure, treatment effectiveness. News release. Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine and Biological Sciences. May 7, 2025. Accessed May 7, 2025.

https://stories.tamu.edu/news/2025/05/07/research-collaboration-takes-one-health-approach-to-study-chagas-disease-exposure-treatment-effectiveness/ - Chagas disease in dogs. Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine and Biological Sciences. April 5, 2018. Accessed May 7, 2025.

https://vetmed.tamu.edu/news/pet-talk/chagas-disease-in-dogs-2018/ - About Chagas disease. CDC. September 4, 2025. Accessed May 7, 2025.

https://www.cdc.gov/chagas/about/index.html#:~:text=About%208%20million%20people%20globally,where%20we%20find%20Chagas%20disease

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.