Advancing treatment of urolithiasis

A Q&A with nephrology and veterinary urology specialist Jody Lulich

Editor's Note: Jody P. Lulich, DVM, PhD, Dipl. ACVIM, is the co-director of The Minnesota Urolith Center and professor of Veterinary Internal Medicine at the University of Minnesota.

DVM: Tell us about The Minnesota Urolith Center.

Lulich: Dr. Carl Osborne started The Center 30 years ago. He had an idea: "War Against Urolithiasis," to offer veterinarians free urolith analysis, and in return, get vital information to improve patient care. He was right on track. In the early years, The Center analyzed only several hundred stones a year. Today, we receive uroliths from more than 60,000 animals annually and from all over the world. The Center is supported in part by an educational gift from Hill's Pet Nutrition.

In our work, we incorporate a team approach in which veterinarians, clients, graduate students, grant organizations, and everyone strives to make a difference in the lives of pets and their owners. We have a mission at The Urolith Center: To make surgical removal of stones a mere historical fact.

DVM: How prevalent are urolith-related disorders in the pet population?

Lulich: While there are no accurate numbers, we estimate 2% to 4% of the pet population globally either have or had stones.

DVM: Are certain types of uroliths more common now than in the past?

Lulich: Yes. Calcium oxalate stones, for example, are more prevalent now than two decades ago, that is, if our workload at The Urolith Center is any indication. We think the reason is multifactorial, with nutritional supplements, medications and breed popularity coming into play.

DVM: What seem to be the most difficult types of uroliths to treat and why?

Lulich: Calcium oxalate is tough to treat because there's no consensus on the underlying causes and risk factors. Currently, we can't dissolve them, and prevention strategies aren't 100-percent effective.

DVM: What advice can you offer veterinarians and pet owners who want to use nutrition to improve management of urolith-related disorders or decrease the risk for recurrence?

Lulich: We tell veterinarians that pets urinate what they eat. Nutrition plays a big part in the solution. We recommend food with high water content, which makes the urine less concentrated. For animals recovering from calcium oxalate stones, owners should avoid feeding foods with high calcium and oxalate and other ingredients that promote calcium and oxalate excretion.

DVM: Have you found any evidence of medications causing urolithiasis in animals?

Lulich: It's interesting that we see stones composed of 100-percent antibiotic. Administration of allopurinol, a drug to treat urate stones, can contribute to xanthine stones. It's important for veterinarians submitting stones to let us know the medications and diet animals were receiving when the stone was diagnosed.

DVM: Are certain breeds most at risk for urolithiasis?

Lulich: It depends on the stone type, of course. But for calcium oxalate, six dog breeds are at greatest risk: miniature schnauzer, miniature poodle, bichon frise, lhasa apso, shih tzu and Yorkshire terrier. Struvite stones primarily form in female dogs.

DVM: Any updates about the melamine and cyanuric acid problem we saw a few years ago, or has that problem been mostly resolved?

Lulich: It's unfortunate that several dishonest suppliers knew tainted ingredients were in not only pet foods but also in human food. It's unlikely we'll see this problem again since pet food manufacturers are more diligent.

DVM: You're known for developing the technique of voiding urohydropropulsion, a nonsurgical method to remove uroliths. Tell us about that and how you devised it.

Lulich: We anesethize the dog, fill the bladder with saline, stand the dog up like a human stands, express the bladder, and in seconds, out come the stones. I do these all the time at the clinic. In 1990, someone brought me a dog to euthanize because it was getting stones. I agreed to take the dog and fix the problem. I thought about the canine anatomy and compared it with human anatomy. A human can pass a stone by urinating standing up. I thought perhaps dogs could do the same. It worked!

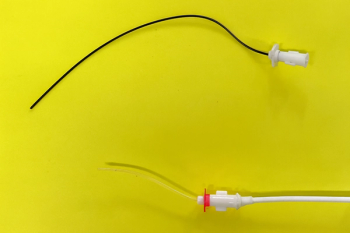

DVM: What kinds of results are being seen with laser lithotripsy?

Lulich: If you don't mind me being a bit folksy: It's a smashing success. Owners love it, because now we have a procedure that eliminates the need for surgery and is less invasive. What's even better than lithotripsy is our ability to medically dissolve struvite stones in cats. For example, we can dissolve these stones in about 10 days with therapeutic diets. This, in turn, has reduced the cost to the client, as well as reduced pain and suffering of the animal. It lets clients know we're a profession that's very compassionate.

DVM: How about with shock wave lithotripsy?

Lulich: Unfortunately, the machines are designed for humans and aren't very adaptable to pets. The focal point is so precise on these machines that, when used for pets, they're just not as effective. Or maybe we're just not effective at using them.

DVM: When should a veterinarian recommend surgery for urolithiasis, and what types of surgery tend to work best?

Lulich: In our hospital, we spend a lot of time utilizing nonsurgical procedures, so I may not be the best person to answer this question, but here goes: The most common reason for doing surgery is to treat a urethral obstruction that can't be removed by any other means. This is especially so in male cats whose anatomy in this regard is so small that using modern extraction equipment simply isn't possible. Numerous stones and large stones are removed faster with surgery. So clients have a choice: minimally invasive or surgical incision.

DVM: Are there any popular misconceptions in the veterinary community about urolithiasis treatment that you'd like to dispel?

Lulich: There's a myth that you shouldn't dissolve stones in males because of fear of obstruction. The truth is that obstruction is possible, but it occurs far less often than predicted. Of course, not all stones can be medically dissolved anyway.

There's also a myth that stones are a disease. The truth is they're the result of pathologic and physiologic factors leading to excessive excretion and precipitation of compounds in the urine to form stones. You have to correct the underlying condition if you want to prevent stone formation.

Donna Loyle is a freelance medical editor and writer in Philadelphia and the former primary editor of the North American Veterinary Licensing Examination.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.