Change maker series: Dr. Scott Campbell

How the CEO of Banfield has rewritten the rules of veterinary practice. ... Part 1 in The Change-Makers Series

Editors' Note: This is the first in a series of articles about change-makers—the thought-leaders who've profoundly affected the business of veterinary practice and whose vision could change average practitioners' career path, business model, or workday in the future.

Dr. Scott Campbell is standing at a big window in his second-floor office at Medical Management International (MMI), the parent company of Banfield, The Pet Hospital. Across Tillamook Street the original Banfield hospital sits in the elbow of three busy roads on this blue-collar side of Portland, Ore. The sky is heavy, the asphalt slick with rain. If the clouds part he'll be looking at Mount Hood.

Below the window, most offices would have a parking lot. Instead Dr. Campbell looks down on the neighborhood dog park he and his staff engineered. Employees park underneath the office building, a 225,000-square-foot brick edifice that serves as the block-long nerve center of more than 600 Banfield hospitals nationwide. Dogs race along the fence above.

Banfield timeline

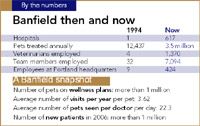

You can learn a lot about how Dr. Campbell's company has grown over the years (see "Banfield Then and Now") by listening to him describe the development of the dog park. First, this park didn't just happen—it was designed. Like everything else under Dr. Campbell's purview, the park is about systems, evidence, and ideas unbounded by conventional wisdom.

The story begins with a problem: Dogs destroy the grass in dog parks. Then comes the need for evidence. His associates studied the way dogs behave and discovered that they run back and forth along fences. Now comes the solution: Build sidewalks next to the fences. That way the turf doesn't turn to mud in the summer. The design, Dr. Campbell says as a small dog romps along the fence below, obviously works.

But the park's crown jewel is the fountain and wading pool in the middle of the four diamond-shaped runs. Both dogs and children frolic in the water in summer, so chlorine is required to protect the kids. But chlorine is bad for dogs. This is the kind of dilemma Dr. Campbell obviously loves. He lays out the problem, pauses, then delivers the punch line.

"So ... we dug a well," he says.

The well ensures that the water is always fresh—no chlorine necessary. The earth washes the water clean as it seeps back into the aquifer. As Dr. Campbell will say a dozen times today, "Everybody wins."

No surprise that Dr. Campbell sees this park as a model for dog parks in cities everywhere. He is equally convinced that Banfield, The Pet Hospital, has captured the model of the future for veterinary practices everywhere.

Of course, not everyone agrees. Dr. Campbell's ideas have never been conventional, safe, or understated. In Banfield's early years, the hue and cry of objection was cacophonous. But no one can dispute the effect he has had on the profession of veterinary medicine. He may be a self-described introvert, but he is not shy about listing the changes he thinks Banfield has fostered. His voice rises when he describes how the Banfield model helps veterinarians build careers and private lives at the same time. In many ways, he has rewritten the rules of veterinary lifestyle for the new century.

You'd have to be practicing veterinary medicine on the moon since 1994 not to know what Scott D. Campbell, DVM, has done with his national practice. Love it or hate it, his contribution has been monumental.

Recently Veterinary Economics sat down with Dr. Campbell to discuss the profession of veterinary medicine, his own journey within that profession, and the changes he's seen in the last decade and a half. Here's what he had to say.

Q. In the early days of Banfield, did you foresee where this practice would go?

A. By 1994, I had a pretty good idea of where it was possible to go. But all the decisions up to that point contributed. You make small decisions and those small decisions create other opportunities. And so you evolve.

So at that point you could see 600-plus hospitals?

More than that. I've always said 2,000, although not publicly. Today I think the number is even higher because we've evolved from being a provider of care to being a provider of management and support services to veterinarians. The doctors in our charter and partner hospitals are the ones providing the care. Very shortly we'll be a billion-dollar company with a thousand hospitals.

I don't know when exactly the original idea started. When I went to veterinary school, I wanted to do a beef cattle consulting practice and some equine. It wasn't until the last half of my senior year that I decided to try small animal. Two years later, after I'd bought the original Banfield hospital from Warren Wegert, I put together a business plan to expand to 14 locations here in Portland.

This all took shape in just two years?

I graduated in 1985. I bought the practice in January 1987, and that year I put together a business plan to create two central clinics and 10 satellite hospitals. I identified the sites and systems we'd need and set out to create those systems. By 1989, I had the systems in place and had moved the original hospital to a new facility. By 1991 that one location was doing about $2.25 million a year and contributing 43 percent to the bottom line. We had located the other sites. Then my wife, Sandy, and I decided we didn't want to do it.

Banfield then and now

Why not?

Because we both grew up in small towns in southeastern Oregon and 43 percent of $2.25 million was more money than we could spend. We were debt-free and investing in real estate, and I was working every other week. We had achieved a tremendously good quality of life.

Instead of following the plan to build these new local hospitals, we decided to license our systems and put them in 12 existing practices around the country. The systems worked great and they helped the veterinarians make money. Despite that, it was hard to convince them to try something new. You can lead a horse to water, but it takes a sedative, twitch, stomach tube, and stomach pump to make it drink. Veterinarians can be the same way. It was very frustrating.

What specifically were you trying to get them to do?

To change the way they practiced and thought. They were used to clients coming in with a problem and then selling them a few shots. This was getting clients to come in for an exam, giving the pet whatever shots it needed, and then finding any disease early in its course so they could do something before it got expensive.

Convincing doctors to get clients to prepay for wellness care was also difficult. Still today people want to focus on illness rather than wellness. Pets who are on wellness plans live about 25 percent longer, according to our research. In addition, clients are winners—they go to veterinarians so their pets will live longer. The team wins, the practice wins, everybody wins.

It was frustrating back then because the systems clearly worked and I wanted to help veterinarians be more successful. I also wanted to help pets live longer. Those were the only reasons for me to license the systems. I certainly did not need the money or the aggravation.

And in those days you had plenty of aggravation.

I got a lot of aggravation. But there were a lot of things that needed to be fixed in veterinary medicine. When the opportunity came up to provide high-quality care by leasing space from PetSmart, I thought that offered a chance to help fix things.

Veterinarians weren't making money then. Graduates were starting at $28,000 a year, and experienced doctors could be hired as associates for $40,000. They were working crazy hours for those kinds of dollars; they didn't have a good quality of life. Plus pets weren't getting the care they needed. So I said, "Well, I'll see if I can put together an organization that can address all that."

Did you make mistakes early on?

Probably the biggest mistake I made was opening 37 hospitals the first year. We believed there were too many veterinarians, but when we got into California we discovered there actually weren't enough. So we opened hospitals with no doctors and hired relief veterinarians to man the hospitals—a fool's game. We couldn't build our brand or assure quality. We really slowed down after that.

We were also too spread out. By the end of the second year we had hospitals all along the West Coast from Bellingham, Wash., to San Diego. Plus we were all over Florida, Chicago, Maryland, and Virginia.

That's a lot of frequent flyer miles.

It's what PetSmart required for us to get the deal. We did what we had to do, but it was difficult to be that spread out. Everybody acted like we were at the bottom of their list of veterinary people they didn't like.

We never intended to go outside the United States, but we have done that now and that will be a big piece of growth in our future. As we leverage our systems over more and more hospitals, it gives us more profit, so we can invest more in the systems.

Are you now doing what you want to do?

When I graduated from veterinary school, my plan was to retire when I was 40. I turned 50 in December, so I haven't made that goal. But I like what I'm doing and I'll continue to do it as long as it's fun. I certainly don't want to do a cow-calf consulting practice any more. I don't want to do equine.

What is your underlying philosophy?

I try to look at the big picture. I try to determine what could be, and what should be, based on the information I have. Then I figure out how to make that happen, regardless—almost exclusively—of what other people think. I try to lead the way rather than sending others out to collect the bullets. I try to get out there in front. If I don't agree with somebody, I let them know. At Banfield, if we shoot someone, we shoot them in the front. We're brutally honest. That's hard for people to get used to, but it's the way we do business. That's how we want to be treated.

From the beginning we've done things the rest of the profession didn't think were right. We've tried to explain what we do and we've listened to people who've convinced us there was a better way to do it, but at the end of the day, we're going to make it happen or die trying.

Most people do things because they want to make money. So they listen way too much to what everybody else says. We try to figure out what should be and go do it, believing we'll be rewarded for it.

That's an interesting idea: Do what should be done and be rewarded for it.

It's like Henry Ford. Somebody asked him what research he did before making the automobile, and he said, "None. If I'd asked people what they wanted, they'd have said a faster horse."

You have to start with a clean sheet of paper. That's why we were so lucky to have the opportunity at PetSmart, because we could design hospitals completely differently than they'd been designed before. We didn't have doctors who were already using other procedures. We said, "We're going to do peer review," where every veterinarian's clinical decisions are periodically reviewed by other doctors. It was no big deal because we built it in from the beginning. If we tried to put peer review into this organization for the first time today, we'd lose 300 doctors.

If you told doctors in an existing hospital that they had to go to a class to learn anesthesia, they'd tell you to get lost. But we don't let our doctors do anesthesia until they've taken a class with us and are certified. We've been able to take anesthetic deaths from the average of about one per 100 in the profession to less than one in 10,000. I've been told that's less than in human healthcare.

You've got to be able to think differently and challenge your paradigms. Most people don't challenge their paradigms. They live within them.

What are some ways Banfield has influenced the profession as a whole?

Veterinarians are making more money. Not just our veterinarians—all veterinarians, largely because we've created change. We've also focused on quality-of-life issues for doctors, and female veterinarians are especially large beneficiaries of what we've done.

Pets are also receiving higher-quality care. When we started expanding in 1994, we had to fire doctors for not giving pain medication for spays or neuters. They just wouldn't do it. Veterinary schools weren't doing it—almost nobody was doing it. We made it a standard. Today, most pets who get surgery receive pain medication. We started that. You can go back and find articles saying how nasty we were, that we were running up the bill. And we didn't even charge for it.

It's hard to imagine now the belief that animals don't feel pain.

But 12 years ago most veterinarians believed that. We caused that change.

Another thing we've done is focus the profession on economic issues. Two years ago we lowered our prices for cat services. Since then we've doubled the number of cats we're caring for. We've shared that information with the industry. We caused a dialogue to start on changes in veterinary school curriculums. Since 85 percent of graduates go into small animal practice, maybe they don't all have to learn how to palpate dairy cows. Last year we paid more than 650 students to work in our hospitals as part of their education. Our goal for this year is 750.

Half your hospitals—48 percent—are less than three years old today. That's a good picture of the size of your growth. Were you ever frightened by growth?

We have good people in this business who've been with us a long time and believe in helping families and the profession.

And that's why you don't worry?

The growth might worry everybody else, but it doesn't worry me. It's what we signed up for. In fact, we have to grow or soon there won't be anyplace for people to work. If you look at the demographics of the profession, you see a huge population of aging owners and outdated facilities that will close in the next 10 or 15 years. As a profession, we have to figure out where the new veterinarians are going to work. Banfield has to build hospitals at an ever faster rate to catch up with the need for places to provide care 10 years from now. I'm not sure we can make that happen.

You often say things that are the opposite of what everybody else is saying. How do you think outside the box?

Everything we do at Banfield is evidence-based. I don't believe something just because somebody says it. I don't care where it's printed; I won't believe it unless I have evidence. Most of what people say is not evidence-based; it's dogma. Doctors have a responsibility to make sure they're telling the truth. In the medical profession—not just the veterinary profession—the pharmaceutical companies have started spoon-feeding doctors what's right and wrong. Doctors have forgotten that they're scientists, particularly in small veterinary practices with one or two doctors who are busier than heck. They don't have time to be scientists. The great thing about Banfield is we have people who can figure these things out. Then we do the right thing. Regardless of what everybody else thinks.

What is the role of the solo practice? Can it exist alongside Banfield?

The great thing about our profession is there are many niches. There will always be a place for individual practitioners who want to own their own practices and have the financial wherewithal to do it—especially if they want to focus on one specific aspect of care or fit a special neighborhood or small town. But it will be more difficult because of heavy debt loads, the high cost of equipment, and more sophisticated licensing boards in the future.

We've found from client surveys that practices shouldn't be too large. We talk a lot about being "neighborly" at Banfield. We've consciously decided that we will limit our hospitals to five doctors. For five doctors you need about 35 staff members, creating an organization of 40. If you get any bigger than that, the organization develops its own bureaucracy and you lose the neighborhood feel. Clients never see the same person twice because the organization is so big. The people we serve want to have a neighborly relationship with their veterinarian.

What do you think is the next big paradigm shift coming in veterinary medicine?

There are several big shifts coming. Because of them there will be more changes in the next 15 years than we've seen in the last 10.

One big change is hospital ownership. Most doctors graduating today don't want to own a practice, and those who do are less able to buy than those who graduated 20 years ago. They have different wants and needs, and they define quality of life differently. Many people who graduated a long time ago dreamed of owning their own practice. Now they're all getting ready to retire, and there are no buyers. So many of the hospitals will just close.

Another big thing—as I said 12 years ago—is that there's an undersupply of veterinarians. The demand for pet care is rising fast, and the supply just isn't. As a result, prices are rising too rapidly and fewer pets are getting care. We did a study last year and found that 60 percent of people with pets have avoided veterinary care in the last year because they were afraid of the prices. If we don't do something about that as a profession, society will.

When human medicine was in a similar crisis, society said, "OK, you guys don't get to provide all the medical care anymore. Practitioners get to do some and physicians' assistants get to do some." That's going to happen to us. Right now we have a monopoly; nobody else can do what we do. It's likely that nurse practitioners or veterinary assistants will be doing wellness exams and vaccinations and some diagnosis and prescribing that isn't being done today.

Something else that's happening is that species other than dogs and cats have gone from a half-percent of practice 12 years ago to 4.5 percent now with a range of up to 15 percent in some general practices. We're seeing a big rise in species that our veterinarians are not really equipped for.

Another change is that our professional liability for making bad decisions or not documenting or forgetting to provide options will become monstrous. We're fooling ourselves by sticking our heads in the sand and ignoring that risk.

The solution for many of those problems is being willing to look at education and to make some sweeping changes, focusing on systems that allow doctors to provide higher-quality care at a lower cost by being more efficient and by practicing as a team, which is what Banfield doctors do. You can't just raise prices. If we continue to raise prices we will become a profession of the elite.

Send comments or questions tove@advanstar.com